We Recommend:

Bach Steel - Experts at historic truss bridge restoration.

BridgeHunter.com Phase 1 is released to the public! - Visit Now

Maple Rapids Road Bridge

Primary Photographer(s): Nathan Holth

Bridge Documented: Summer 2005 - September 7, 2013

Rural (Near Maple Rapids): Clinton County, Michigan: United States

1888 By Builder/Contractor: Variety Iron Works of Cleveland, Ohio

Not Available or Not Applicable

93.0 Feet (28.3 Meters)

93.0 Feet (28.3 Meters)

14 Feet (4.27 Meters)

1 Main Span(s)

19308H00012B010

View Information About HSR Ratings

Bridge Documentation

This bridge no longer exists!

This bridge's song is:

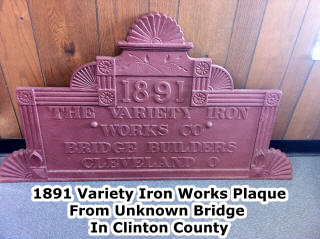

Additional Information: The plaque pictured below was reportedly from a bridge over Stoney Creek on Tallman Road which was removed May 22, 1985.

View Archived National Bridge Inventory Report - Has Additional Details and Evaluation

This 125 year old historic bridge collapsed 2:00 PM EDT, April 4, 2013 and was scrapped out September 7, 2013!

View The Historic Bridge Inspection File For This Bridge

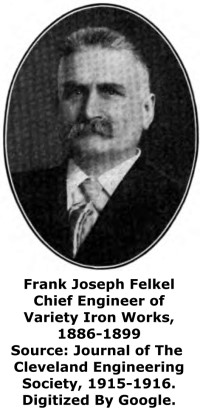

View A Collection of Historical Articles About The People of Variety Ion Works

Description, History, and Significance of Bridge

This bridge has a standard pin connected Pratt truss configuration, but it also has a number of unusual and noteworthy details. The bridge has built-up floor beams with an attractive shape to them. The sway bracing is also an unusual design. There is lattice on the top of the top chord which is especially rare. The bottom of the top chord has the more common battens. Another oddity is that the end post is not the same design as the top chord: the end posts have a cover plate riveted on the top side which is the more common design. The corners of the portal bracing have circles inside them, adding a strong decorative aspect to the bridge. At five panels, this is a relatively short through truss. This bridge is the last example in Michigan built by the Variety Iron Works from Cleveland, Ohio. It was built in 1888, according to the Historic Bridge Inventory. The county road commission did have an 1891 Variety Iron Works bridge plaque at the county road garage (see photo to left), which at first made it seem like the bridge may have been built in 1891. However a resident who lived near the Maple Rapids Road Bridge clearly recalled that the plaque on the Maple Rapids Road Bridge (which was stolen years ago) said 1888. He also commented that the bridge was closed to traffic ca. 1984. The 1891 plaque must have been from another long-lost Variety Iron Works bridge in Clinton County. Some counties did often do repeated business with a bridge builder, if they had a good experience the first time. This may explain why a bridge builder that was not very large in size and was not known to be prolific in Michigan ended up building two bridges in Clinton County. Also of note, the 1891 plaque as seen to the left has the aesthetic details of a plaque from the Buckeye Bridge Works of Cleveland, Ohio, this is likely because Variety Iron Works purchased that company in 1888, and likely adopted their plaque design. Learn more about the history of the Variety Iron Works further down this page.

It should also be noted that Maple Rapids used to have another truss bridge in town, however it appears that this other bridge was not the work of Variety Iron Works. Photos of the bridge appear in the local bar at Maple Rapids, and one photo is shown on this page to the right. Vern Mesler provided this additional, much clearer photo as well. This bridge was similar to the Six Mile Creek Road Bridge with a similar, distinctive portal bracing design and a lack of struts (lateral bracing only) overhead, so was undoubtedly the work of the Morse Bridge Company of Youngstown, Ohio.

Early April 2013 Bridge Collapse and Early September 2013 Bridge Scrapping/Salvage

It would have seemed logical to preserve this truss bridge because it is located in a state game area, where it could have served foot traffic. Unfortunately, preserving closed truss bridges in state parks rarely happens in Michigan. The Ford Road Bridge and the Turner Road Bridge are both examples of bridges in state game areas that were abandoned with no restoration. When these bridges collapse, it makes it very inconvenient to access the areas across the river. Restoring these bridges would have helped unite the park and also preserve a rare and beautiful part of Michigan's transportation heritage.

Since 2006, HistoricBridges.org warned that this bridge was at risk of collapse and should be moved off its abutments to save it from destruction. HistoricBridges.org tried to seek out new owners who would have relocated and preserved the bridge elsewhere. However, nobody took action soon enough, and at 2:00 PM EDT on April 4, 2013, after standing for 125 years and defying gravity on faulty abutments for at least six years, one of the last surviving bridges built by the Variety Iron Works... and the only one in Michigan... collapsed into the river during a windy day with high water levels. The collapse was the completely the fault of the stone abutments. Enough stones washed out that they were unable to support the superstructure. An iron truss superstructure in a condition that would have been easy to restore was destroyed by crumbling abutments. Frank Fick was actually there checking on the bridge when the collapse happened. He reports that the stones from the abutments could be heard plopping out into the water as the wind blew, and then after about 20 minutes, with a final gust of wind the bridge "folded over" almost in slow motion.

After it collapsed, it may have still been possible to carefully remove the bridge and salvage enough intact parts of the bridge that coupled with replication of some parts, the bridge could have been restored. However, no action was taken by anyone, and then the bridge was dragged out by a subcontractor that the county road commission hired. The county road commission thought this subcontractor would take the bridge out in a halfway respectable manner, but instead the subcontractor removed the bridge in a messy manner (to put it politely) and and dumped in a pile on the ground, turning a potentially salvageable bridge into a ruined pile of wrought iron. The only remotely good news is that the county road commission did agree to donate the bridge materials for historic bridge research. The connection assemblies on the bridge were salvaged and will be used for historic bridge research, presentations, and demonstrations. Most of the rods on the bridge were also salvaged and will be sold to researchers and blacksmiths who wish to work with wrought iron along with an informative pamphlet explaining where the material came from. The remainder of the bridge was scrapped out and the money will be going to a scholarship fund for the Lansing Community College's 2014 Iron and Steel Preservation Conference.

A number of Michigan's metal truss bridges like this one were built on random rubble abutments. These abutments appear to have been built by local farmers who took stones dug out of fields in the area, piled them up along the river and jammed some mortar in. While they may look quaint and historic, they are far more poorly designed than coursed ashlar that was popular in states like Pennsylvania. If bridges are to be preserved in place, HistoricBridges.org suggests that if funding allows, drastic action like encasing random rubble abutments in concrete or replacing them entirely may be wise for the sake of preserving the historic truss. Otherwise, the best option may be to lift the bridge off the abutments and place the bridge on the ground until funding for new abutments becomes available. Unlike coursed ashlar, random rubble abutments have little ability to hold themselves together once the mortar begins to deteriorate. Whatever historic significance these poorly built abutments have does not justify putting a historically significant truss at risk.

Finally, the author of this website is quite distressed by the loss of this bridge, having invested years into trying to talk many people into saving the bridge, warning of its impending collapse. Like checking on a dear friend in the hospital on life support, the author of this website visited the bridge personally any time river levels reached a certain flood level to check on the bridge and see if it was still standing, a task aided by a USGS gauging station a mile from the bridge. Michigan has many people who care about historic metal truss bridges, and Michigan even became home to the first historic bridge park. Much research into the restoration of historic truss bridges takes place in Michigan. A number of truss bridges were years ago put into storage and await restoration in the future. Why could this bridge have not been saved in a similar manner? A couple potential new owners for the bridge did step forward with interest in the bridge, but these never resolved to an actual relocation project in time. To rub salt on the wound, in July of 2013, about a month before this bridge collapsed, a covered bridge in Ionia County was destroyed in a fire and this bridge got a far better treatment following destruction. You would not believe the outcry this caused! And full television coverage by television stations across the state! Immediately people banded together and started raising money to salvage the surviving parts in the river and committed to rebuilding the bridge as a replica. The poor Maple Rapids Road Bridge did not get this level of attention. And why? Probably because it wasn't a covered bridge. Its great that covered bridges get so much love and attention, but metal truss bridges like the Maple Rapids Road Bridge are just as deserving, yet they are given comparatively little attention. This is why HistoricBridges.org has chosen to spend its limited time and resources documenting historic bridges types other than covered bridges, in hopes of raising awareness of other historic bridge types. Unfortunately, this effort did little to help the Maple Rapids Road Bridge. Ironically, it was the collapse of another abandoned truss bridge due to failure of similar random rubble abutments that collapsed in 2002 on another state game area and prompted the creation of the website that is today HistoricBridges.org. This bridge was the Ford Road Bridge. The loss of the Maple Rapids Bridge is so strikingly similar to the loss of the Ford Road Bridge that it was a rather ironic and sad event to occur on the 10th Anniversary of HistoricBridges.org.

Photos documenting the bridge collapse and scrapping out are available in a photo gallery. This photo gallery even has photos submitted by Frank Fick who was lucky (or unlucky) enough to actually witness the bridge collapse!

Discussion of Bridge Condition in 2006

It could be gone tomorrow, or it might stand for another decade. The reality is that one of the next few spring floods will most likely spell the end for this unusual and beautiful bridge. The loss of this unique bridge will be a tragedy. This bridge is technically already half collapsed in that one corner of the bridge has dropped six to twelve inches. This is due to a major portion of the stone abutments being washed away. The result was that the bridge had nothing to sit on in its southeast corner, and that corner fell to a spot where there was still something to sit on. This drop resulted in damage to the rest of the bridge. Specifically, some of the deck stringers came loose. The original pole guardrails on the east side of the bridge were bent up a little. Bottom chord eyebars on both sides of the bridge are bowed out. The portal bracing was bent as well. Needless to say, there are now parts of the bridge that are under more tension or compression that they were designed for, and the bridge itself might eventually break apart further even if the abutments do not deteriorate further.

History of the Variety Iron Works

The Variety Iron Works was an aptly named company, since they built far more than just bridges, with a portfolio ranging from fire grates to observation towers. The Historic American Engineering Record presents a short history below.

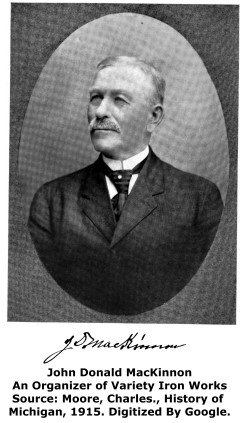

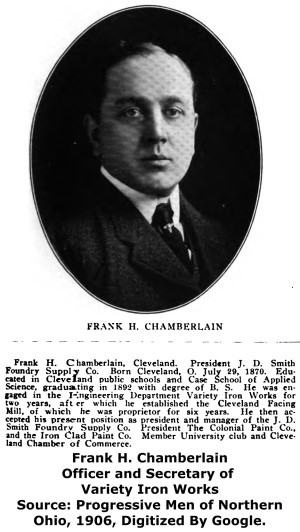

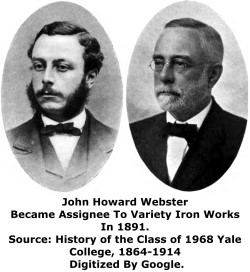

The Variety Iron Works Company was first listed in the Cleveland city directory in 1867. In 1872 the officers were C. F. Olds, F. L. Chamberlain, and Lucius M. Pitkin, who remained with the company for many years. The works was located on Scranton Road at the Brie Railway tracks on the west side of the Cuyahoga River in the industrial valley of Cleveland, where the company made boilers, tanks, heavy sheet-iron, fire grates, pulleys and hangers. By the 1890s, when it built the Gettysburg observation tower, a second works had been opened on the east side of Cleveland on the Pennsylvania Railroad, for the fabrication of bridges, roofs, iron and steel buildings, architectural work, and hoisting and conveying machinery. At that time Cleveland was the leading center in the country for the production of heavy machinery. The Hamilton Avenue buildings of Number 2 works are still partially intact. Before 1912 the company became the Variety Iron and Steel Works, J. H. Webster, president. The company remained active throughout the 1920s, but was apparently a victim of the Depression, since it does not appear in the city directory of 1934. Source: Historic American Engineering Record HAER: PA-1776

Another history from Historic American Engineering Record appears in another documentation:

The Variety Iron Works Company was incorporated in 1866 with a capital stock of $60,000 and increased its capitalization to $200,000 in 1886. The 1888 directory The Industries of Cleveland noted that Variety Iron Works fully lived up to its name, manufacturing "steam boilers of all kinds (marine, locomotive, stationary and portable)" as "a specialty in which the works have achieved deserved fame", but also making "a general line of plate, sheet, wrought and cast iron work" including tanks, stills, smokestacks, breeching, forgings, machinery, shafts, pulleys, hangers, light and heavy castings, shaking grates, Butman fire fronts and automatic doors, railroad crossings, frogs, switches, switch stands, track supplies, and tie-bars. Variety's main plant, at Scranton Avenue and Carter Street in Cleveland, burned during the city's great fire of 1884, but was rebuilt "on a much more extended scale" making the firm "one of the largest, completest and most comprehensive boiler works, machine shops, and foundries in the country."

In 1888, the company was led by LM. Pitkin, President, and F.L. Chamberlin, Secretary; Pitkin "had personal supervision of the works." The firm also owned the Cleveland facing mills and was ready to fill orders for seacoal, charcoal, stove plate facings, foundry supplies, crucibles, shovels, steel and brass riddles, moiders' tools, fire brick, and day. A work force of 220 labored at Variety in 1888; by 1893, the total number of workers was 350. Research indicates that the company expanded into fabrication of metal truss bridges after the main plant was rebuilt in the wake of the fire of 1884.

The 1888 industrial directory observed that "the company has recently purchased the Buckeye Bridge and Boiler Works, at Hamilton street near Case Avenue, and are already engaged in building bridges," Reflecting the firm's foray into bridge building, a third key company officer in 1893 was Charles F. Lewis, the firm's chief engineer and superintendent. An 1898 Engineering News advertisement noted that Variety Iron Works then worked in the "three B's: bridges, buildings, and boilers." Iron and steel directories of the period indicate that the Variety Iron Works was active in the manufacture of bridges from 1888 through at least 1901; no records have been found indicating the date when the company ceased operations. Source: Historic American Engineering Record HAER: VA-1743

According to a forum post on Bridgehunter by Gerry McGuire, his grandfather, J.P. McGuire was a metallurgical engineer who was president of Variety Iron Works for a time. McGuire died in 1908 and the company was apparently bought by two gentlemen, one with the last name of Mathers and the other with the last name of Pitkin (likely former officer Lucius M. Pitkin). According to Gerry McGuire, the company eventually became Interlake Steel.

Remaining Variety Iron Works Bridges

There are currently only about a handful or so other bridges known to remain in the country built by the Variety Iron Works. Bridges photographed by HistoricBridges.org are the Valley Crossroad Bridge in Pennsylvania, the Red Mills Bridge (closed, future uncertain) in Pennsylvania, and the Caldwell Road Bridge (abandoned, future uncertain) in Ohio. The Iron Bridge Road Bridge in Pennsylvania was demolished. Finally, a couple others are identified over on BridgeHunter.com.

Other Variety Iron Works Structures (Both Demolished and Extant)

True to its name, the company built a variety of structures beyond bridges. There are some observation towers in Gettysburg National Park that they built as well as one as Valley Forge. The Valley Forge Tower was demolished, but a couple of the Gettysburg towers remain, although one is altered. One example is shown below. The company also built some lighthouses as Volume 69 of Steel and Iron indicated, one at the Sturgeon Bay Canal and the other at Devil's Island both along Lake Michigan in Wisconsin. Another was erected at North Manitou in Michigan. The article which includes drawings is available here. The towers were an experimental design, and they turned out to be too slender and needed additional bracing added. Built in 1898, the Sturgeon Bay Canal tower was altered in 1903 to fix vibrations in the tower. Diagrams for the Sturgeon Bay Canal structure show steel buttress-like additions were attached to the tower from the base up to the light. At the base, the original curved lattice buttresses were expanded as well to accommodate this.

|

|

| Above: Longstreet Tower, Gettysburg. | Above: Sturgeon Bay Canal Light. Photo Credit: Anne Hornyak, CC BY-SA 2.0 |

Information and Findings From MDOT

The Variety Ironworks of Cleveland, Ohio, was one of several medium-sized companies that built metal truss bridges throughout the midwest in the nineteenth century. This is the only known surviving example of this firm's work left in Michigan.

|

This bridge is tagged with the following special condition(s): Unorganized Photos

![]()

Photo Galleries and Videos: Maple Rapids Road Bridge

2009 Documentation

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos, with a focus on details. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2009 Documentation

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos, with a focus on details. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Earlier Visits and Winter Gallery

This gallery includes beautiful winter photos of this bridge and all other earlier documentation of the bridge as well. A focus on overview photos is present here. This photo gallery contains a combination of Original Size photos and Mobile Optimized photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

February 2011 Visit

Original / Full Size PhotosA brief assessment of the bridge and site conditions in early 2011 with deep snow on the ground. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

February 2011 Visit

Mobile Optimized PhotosA brief assessment of the bridge and site conditions in early 2011 with deep snow on the ground. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

April-September 2013: Collapse and Scrapping Out

Original / Full Size PhotosPhotos of the bridge after it collpased in April 2013 and photos of the bridge being scrapped out in September 2013. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

April-September 2013: Collapse and Scrapping Out

Mobile Optimized PhotosPhotos of the bridge after it collpased in April 2013 and photos of the bridge being scrapped out in September 2013. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2013 Additional Unorganized Photos

Original / Full Size PhotosA supplemental collection of photos that are from additional visit(s) to the bridge and have not been organized or captioned. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2013 Additional Unorganized Photos

Mobile Optimized PhotosA supplemental collection of photos that are from additional visit(s) to the bridge and have not been organized or captioned. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

North Site Conditions

Full Motion VideoA short pan around showing conditions as seen from the north side of the bridge, taken prior to collapse. Streaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

South Site Conditions

Full Motion VideoTaken prior to collapse, a short pan around showing conditions south of the bridge as seen from the north side of the bridge. Also shows the truss. Streaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Maps and Links: Maple Rapids Road Bridge

This historic bridge has been demolished. This map is shown for reference purposes only.

Coordinates (Latitude, Longitude):

Search For Additional Bridge Listings:

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) of this bridge.

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 10 miles (16 kilometers) of this bridge.

Additional Maps:

Google Streetview (If Available)

GeoHack (Additional Links and Coordinates)

Apple Maps (Via DuckDuckGo Search)

Apple Maps (Apple devices only)

Android: Open Location In Your Map or GPS App

Flickr Gallery (Find Nearby Photos)

Wikimedia Commons (Find Nearby Photos)

Directions Via Sygic For Android

Directions Via Sygic For iOS and Android Dolphin Browser

USGS National Map (United States Only)

Historical USGS Topo Maps (United States Only)

Historic Aerials (United States Only)

CalTopo Maps (United States Only)