Official Heritage Listing Information and Findings

Listed At: Grade II*

Discussion:

List Entry Number: 1248569

Summary

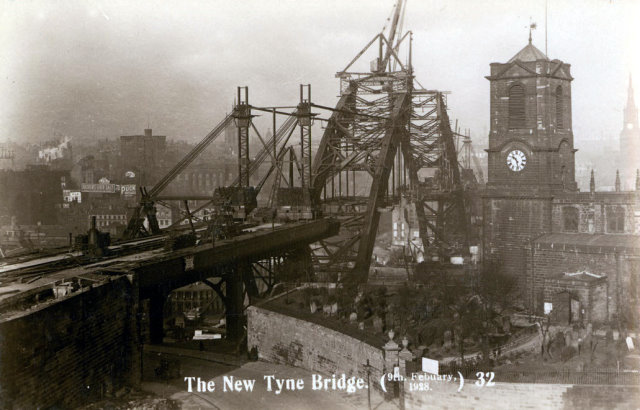

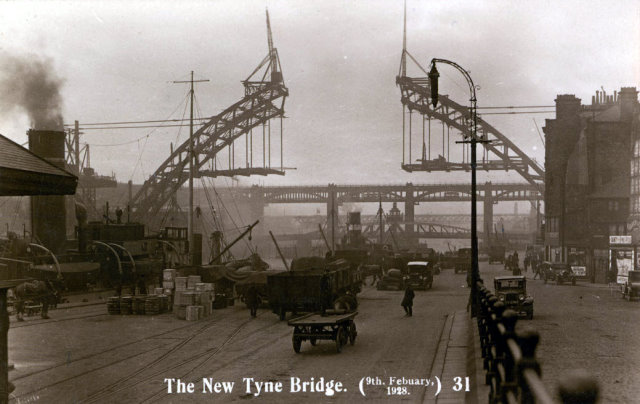

Single-span steel arch road bridge, 1925-28 to designs by engineers

Mott, Hay and Anderson; abutment towers to designs by R Burns Dick.

Constructed by Dorman, Long & Co Ltd of Middlesbrough with Ralph Freeman

as consulting engineer.

Reasons for Designation

The New Tyne

Bridge of 1928, is listed at Grade II* for the following principal

reasons:

Architectural interest:

* a striking steel arch

design, notable as the largest single-span steel arch bridge in Britain

at its construction;

* a scaled-down version of the similar

design prepared for Sydney Harbour, Australia with a main arch designed

by the eminent civil engineer (Sir) Ralph Freeman;

* the

prototype of a method of construction involving progressive

cantilevering from both sides of the river using cables, cradles and

cranes, developed for Sydney Harbour but tested first at Newcastle;

* elegant pylons incorporating towers that are well-detailed with

both neoclassical and Art Deco influences;

* recognised

world-wide for its dramatic design which has become the potent symbol of

the character and industrial pride of Tyneside.

Historic

interest:

* associated with some of the most distinguished

early-C20 civil engineers including Sir Ralph Freeman, designer of some

of the world's most impressive bridges, and founder of Freeman Fox &

Partners, internationally renowned bridge designers.

Group

value:

* the High Level Bridge (Grade I), the Swing Bridge (II*)

and the New Tyne Bridge, augmented by the addition in 2001 of the

Millennium Bridge (unlisted), taken together provide one of the most

evocative and dramatic river-crossings in England.

History

The

idea of a high level road bridge to align with the Great North Road and

carry traffic across the River Tyne without having to descend to river

level had been discussed as early as 1860. A proposal in 1921 by local

civil engineer T M Webster, was agreed by the town corporations of

Newcastle and Gateshead in 1924. The project was encouraged by the

prospect of a large Government subsidy on the basis that it would help

alleviate chronic unemployment on Tyneside, especially in the

shipbuilding industry. London consulting engineers Mott, Hay and

Anderson was asked to provide an appropriate design, and Royal Assent

was granted for the necessary Act of Parliament on 7 August 1924. Five

companies tendered for the construction contract, which was awarded in

December 1924 to Dorman, Long & Co Ltd, of Middlesbrough, with Ralph

Freeman as their consulting engineer. Robert Burns Dick designed the

bridge pylons, which were originally intended to be significantly

taller. The Tyne Improvement Commissioners required that the new bridge

should have no river piers and should allow full navigational clearance

across the entire width of the River Tyne during and after its

construction, and that no material should be allowed to be lifted from

the river on floating barges. This requirement ensured that a dramatic

single-span bridge with a level deck would be designed by an equally

dramatic method of construction.

A similar but larger-scale

project had already started by the same contractors working with the

same consultant at Sydney Harbour, Australia. That scheme had been

awarded to Dorman Long in March 1924, with a design by Freeman based on

the Hell Gate Bridge in New York. The Sydney Harbour Bridge was to be a

single-span, two-hinged, steel-arch bridge, flanked by granite-faced

pylons, with a span of 1,650 feet, carrying a suspended deck at a height

of 172 feet above the water. Mott, Hay and Anderson’s Tyne Bridge design

was to be similar to that for Sydney Harbour, with a span of 531 feet

(162m) and a road deck 85 feet (26m) above high water mark. Construction

of the New Tyne Bridge began in August 1925, and the requirements of the

Tyne Improvement Commissioners also led to the adoption of the novel

constructional method Freeman had developed for Sydney Harbour, where

the deep waters there did not allow the use of any temporary

construction supports. The erection of the Newcastle arch by

cantilevering was undertaken progressively from each side of the river

using cables, cradles and cranes, and provided Dorman Long with a test

bed for these and other items envisaged for eventual use on Sydney. It

is thought that this was the first use of such a construction method in

this country. The bridge was built like a ship using shipbuilding

techniques with rivets and panels welded together. The bridge builders

scaled the heights without the benefit of safety equipment, and one man,

Nathaniel Collins a scaffolder from South Shields, fell from the bridge

and lost his life during its construction.

The New Tyne Bridge

was completed on 25 February 1928, almost four years before completion

of Sydney Harbour Bridge. It joined other Newcastle-Gateshed Tyne river

crossings including the High Level Bridge (1849; National Heritage List

for England or NHLE: 1248568, Grade I); the Swing Bridge (1868-1876;

NHLE: 1390930, Grade II*) and King Edward Railway Bridge (1902-6; NHLE:

1242100, Grade II). This important group of bridges has since been

joined by others including the Millennium Bridge (2001). At the time of

opening the New Tyne Bridge was the largest single-span bridge in

Britain, and had been constructed at a total cost of £1,200,000. The

bridge, having been painted green with paint supplied by J Dampney Co of

Gateshead, was opened on 10 October 1928 by King George V, accompanied

by Queen Mary. The King and Queen were the first people to use the

roadway, riding across in their Ascot landau, and the King's opening

speech was recorded by Movietone News. Some 2,000 local school children

were given a day off school to attend the opening ceremony, and

presented with a commemorative brochure. The new bridge received much

positive attention in local and national press and in specialist

journals.

Dorman Long & Co Ltd was formed in 1875 in the

north-east of England as steel makers, constructional engineers and

bridge builders, and went on to construct many of the most famous

bridges built in the first half of the C20 including the Sydney Harbour

Bridge (1932), the New Tyne Bridge (1928), the Tees Newport Bridge

(1934) and the Omdurman Bridge (1926, Sudan). Sir Ralph Freeman is a

nationally renowned civil engineer whose most important work is

considered to be his design work in connection with Sydney Harbour

Bridge. A paper given on the subject of its design and foundations by

Freeman to the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) in 1934 led to the

award of a Telford gold medal for the paper and the first Baker gold

medal in recognition of the development in engineering practice as

described by the paper. Mott, Hay & Anderson was established in 1902,

and when they were awarded the Tyne Bridge contract they were

distinguished and experienced in the planning of large engineering

projects. After a merger in 1989 to become Mott MacDonald, their

portfolio expanded to include prominent schemes such as the Tyne & Wear

Metro and the Tyne Tunnel. Robert Burns Dick (1868-1954) was a notable

regional architect, who in 1899 entered into partnership with James

Cackett. He was admitted FRIBA on 8 January 1906. Burns Dick has a

varied portfolio in terms of building type, style and function, very

many of which are listed on the National Heritage List for England

including the Grade II Spanish City (1908-10, NHLE: 1025339) and the

Neo-Jacobean Newcastle University Students Union building (1924, NHLE:

1355263).

While New Tyne Bridge is its proper name, whether this

was to distinguish it from the Old Tyne Bridge (a medieval bridge that

was mostly destroyed by floods in 1771, NHLE: 11003513 and 1323141) or

simply because at the time of construction it was the new bridge over

the Tyne, is not clear. The bridge is now known as the Tyne Bridge.

Details

Single-span steel arch road bridge, 1925-28 to designs by

engineers Mott, Hay and Anderson of Westminster; abutment towers to

designs of Robert Burns Dick. Constructed by Dorman, Long & Co Ltd of

Middlesbrough under supervision of Charles Mitchell, with Ralph Freeman

as consulting engineer.

MATERIALS: steel arch; steel columns and

stone walls supporting the road approach; the pylons have solid concrete

abutments with steel and concrete towers, clad in granite; the bridge

parapet is cast iron.

PLAN: single-span, two-hinged steel-arch

with a pylon at either end, carrying a suspended deck; land approaches

to either end.

EXTERIOR: the steel arch is of two-hinged form

constructed from two main mild steel parabolic trusses, each consisting

of two arched ribs 14m apart between centres, connected by a single

system of web members with Warren-type bracing in the form of simple

diagonals. The arch spans 162m and rises to a height of 55m. It carries

a 17m wide suspended deck some 26m above high water level, incorporating

cantilevered footways to either side. The deck within the arch consists

of cross-girders suspended from the trusses by a series of hangers

formed of steel members, and on the approaches the deck rests on

spandrel columns rising from the top of the trusses. Beneath the deck

are enclosed ducts containing water and gas mains and electrical

services. The arch is secured by 12 inch (30cm) diameter pins to a land

abutment on either side of the River Tyne, which bear the thrust of the

arch, and are carried down to bedrock with solid concrete bases.

Above each abutment is a steel and concrete rectangular-plan tower,

faced in granite, comprising a five-storey central part with taller

projections to the east and west sides. The towers have neoclassical

detailing to the tops and very tall arched recesses to the outer faces

containing a continuous sequence of alternating windows and aprons, with

bracketed balconies. They are also considered to be Art Deco influenced

seen in the overall massing and the plinth level door cases featuring

over-sized keystones. Original doors are mostly retained, but original

metal-framed windows have largely been replaced with timber versions,

with the exception of three ground floor windows to the south tower in

which original metal frames remain.

The approach spans are

carried partly on earth filling between retaining-walls and partly on

continuous plate girders supported by two pairs of octagonal steel

columns on the Newcastle side, skewed to accommodate the street plan

below, and a single pair in line on the Gateshead side. The panelled

cast-iron parapet on the arch and the approach spans, with lamp

standards mounted at intervals, is by Macfarlane & Co of Glasgow.

INTERIOR: the central part of each tower was intended to serve as

warehouse space (unused), with passenger lifts in the west projection

and pedestrian stairs and goods lifts in the east projection. Lifts and

stairs provided access from ground level to bridge deck level with

vestibules at both levels.

NORTH TOWER: the warehouse section

has a skeletal steel framework of joists, main beams and supporting

columns for the intended floors which were never installed. The public

stair hall has a concrete dado and staircase, the latter with stick

balusters, an octagonal newel post with an ornate finial, and a ramped

hand rail, all of cast-iron. The stair rises to deck level where an

arched entrance opens into a rectangular lobby with concrete coving, a

cast-iron lantern and an original exit/entrance; the latter is fitted

with original double doors and a decorative fanlight of semi-circular

tracery. The public lift hall has ground floor and deck level lobbies,

each with cast-iron lanterns above each of the two sets of double,

panelled lift doors, the latter with monolithic granite surrounds; one

set of lift doors to each lobby retains original 36-pane leaded upper

lights. The upper lobby also has an opening with identical doors and

fanlight to that of the deck-level stair hall, and there is an Art

Deco-style sunburst design; one of the lifts has an original lift

mechanism housed within a small cupboard. The lower lobby retains part

of what is considered to be an original Art Deco mural featuring

steamers. The two original passenger lifts remain within the lift shaft,

both with timber panelled interiors with decorative lozenge and oval

detailing, and metal lattice doors. A small room to the rear of the

upper lift lobby retains the original lift motors, which are marked 'The

Express Lift Company, London'.

SOUTH TOWER: this retains a

similar skeletal framework as that to the north tower, and has shafts

for lifts that were never installed. The public stair hall, staircase

and vestibule are similarly detailed to that of the north tower.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()