We Recommend:

Bach Steel - Experts at historic truss bridge restoration.

BridgeHunter.com Phase 1 is released to the public! - Visit Now

McMillin Bridge

Primary Photographer(s): Nathan Holth

Bridge Documented: August 24, 2014

Rural: Pierce County, Washington: United States

1934 By Builder/Contractor: Dolph Jones of Tacoma, Washington and Engineer/Design: W. H. Witt Company of Seattle, Washington and Homer M. Hadley

Not Available or Not Applicable

170.0 Feet (51.8 Meters)

210.0 Feet (64 Meters)

22 Feet (6.71 Meters)

1 Main Span(s) and 2 Approach Span(s)

000000JD0000000

View Information About HSR Ratings

Bridge Documentation

View Archived National Bridge Inventory Report - Has Additional Details and Evaluation

View Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Documentation For This Bridge

HAER Drawings, PDF - HAER Data Pages, PDF

View Historic Structure Reports For This Bridge

View Historical Article About This Bridge

View Original Plans For This Historic Bridge

A Unique, Nationally Significant Historic Bridge

The McMillin Bridge is one of only a few known concrete truss bridges in the United States. Of those that survive, no other concrete truss bridge looks even remotely like the McMillin Bridge. The McMillin Bridge has a very long span, and massive trusses. It was the longest span of its kind in the world when completed. Its trusses are so massive that a creative placement of the sidewalk was utilized on this bridge. Rather than employ a cantilevered sidewalk, or a sidewalk on the inside of the truss lines which would have reduced the roadway for vehicles, the sidewalks of this bridge pass right through the middle of each truss line. This is possible because the diagonal members are configured as pairs of beams side-by-side, and the vertical members are essentially solid pieces of concrete with openings that pedestrians can walk through. Another unusual feature of the sidewalk is that it has a wooden deck. Wooden decks are almost unheard of on concrete bridges. The steel pipe railings on the bridge are also a feature that are also somewhat uncommon on concrete bridges, which usually had concrete railings.

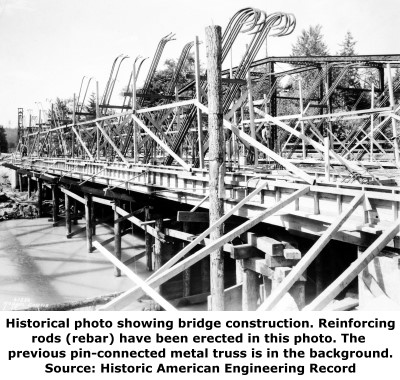

To clarify the design of the McMillin Bridge, it is an genuine reinforced concrete truss. It is not a concrete encased metal truss bridge. It utilizes reinforcing rods (rebar) for its internal support system, just like the majority of reinforced concrete bridges.

The W. H. Witt Company of Seattle prepared the plans for the bridge, but engineer Homer M. Hadley came up with the general concept for this concrete truss bridge. Hadley is known as the most significant Washington State bridge engineer... in addition to this concrete truss, he designed an unusual and early cable-stayed bridge and also the world's first concrete pontoon (floating) bridge.

The bridge retains excellent historic integrity with no major alterations to the original design noted. It also retains excellent structural integrity with no major concrete deterioration noted.

For more information about the history and design of this bridge, please browse the impressive Historic American Engineering Record documentation, whose links are available at the top of this narrative.

So Unique It Defies Classification

The bridge is so unique it is hard to classify. Some of the problems in classifying the bridge are noted below.

The top chord is 2.5 feet taller in the center than at the ends. This is a very slight amount of variation. Some sources described the bridge as having a curved top chord. However the original plans for the bridge do not define a radius for the top chord (which is how curves are usually shown on plans). A camber is shown for the bottom chord, but not the top chord. Instead, the truss depth at each panel is shown, more typical of how a polygonal top chord composed of straight sections at different angles might be shown. Indeed, this evidence indicates that the bridge is polygonal and not curved. The next challenge is whether the polygonal portion, which as mentioned is extremely subtle, would be enough to justify calling it a Parker truss. Most sources simply describe the bridge as a Pratt. As the Parker is a form of Pratt, neither description is incorrect. Its almost a matter of opinion whether the polygonal aspect of this bridge is notable enough to classify it as a Parker or not.

Another element of the bridge that is difficult to classify due to the unique nature of the bridge is how many truss lines it has. HAER describes the trusses as double trusses, and the reason for this is obvious... when you consider that you can walk through the truss's members, with concrete members to your left and right as you do so, it does feel like their is one pair of trusses next to each other on each side of the bridge. However, the vertical members could also be interpreted as single members with holes cut in them to admit pedestrians. And the pairs of diagonal members at each panel point could be compared to the pairs of eyebars found on diagonal members of pin-connected metal truss bridges. So a solid argument for the bridge consisting of a single truss line on each side of the bridge could be made also.

The Long Road To Preservation

It is a threat a historic bridge should never have to face. A proposal to build a new replacement bridge on a new alignment, to also be followed by the demolition of the historic bridge, even though the bridge is in good condition and not in the way of its replacement. Yet this is the threat that the McMillin Bridge faced for many years as WSDOT worked to develop a project to address the narrow lanes of this bridge. Why would anyone want to spend this nation's limited tax dollars to destroy a historic bridge that remains in good physical condition and is not in the way of its replacement? There really is not a good answer, especially with a bridge that is one of only a few in the country, is nationally significant, and was designed by its state's most noteworthy bridge engineer. When WSDOT proposed to build a new bridge and then demolish this bridge afterwards, this triggered a Section 106 Review, and because of the national significance of this bridge, the review attracted the interest of historic experts from not only Washington State, but from across the country, who all became consulting parties for the Section 106 Review. Among the consulting parties were HistoricBridges.org, the Historic Bridge Foundation, and even a former WSDOT bridge engineer. The critical question from day one was why did WSDOT need to demolish a historic bridge that was in good condition and not in the way of its replacement? For literally years discussions went back and forth. The best arguments WSDOT could provide were unable to hold up to scrutiny in the eyes of the consulting parties. WSDOT claimed the length of the historic bridge was not long enough to accommodate flood waters. Yet there was no evidence of damaging floods in the past, and additionally the historic railroad truss bridge that today carries the Foothills Trail actually has an even shorter span, and therefore would be the controlling structure for how much river water can get through this location. WSDOT claimed that it could not be responsible for maintaining a historic bridge that had been bypassed by a historic bridge, even though the Indian Timothy Memorial Bridge was an example of just that. WSDOT claimed it would be costly to maintain the bridge for pedestrian use, even though such claims are unsubstantiated as the bridge is in good condition and once vehicular traffic ceases to cross the bridge, wear and tear would be minimal.

WSDOT strongly desired to move the project forward after years of arguing in the Section 106 process. The consulting parties suggested a novel idea. Simply redefine the project contract to include constructing the new bridge and simply remove the demolition portion of the project from the contract... this would eliminate the need for any Section 106 Review. WSDOT agreed to this idea, and Section 106 Review was ended with WSDOT deciding to eliminate demolition from the contract. Interestingly however, Washington State has a special state level regulation for historic structures called Executive Order 05-05 which requires coordination of projects with Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP), the Governor�s Office of Indian Affairs (GOIA). Because the proposed project constructs a new bridge very close to the historic bridge, and because there is the risk for the historic bridge being neglected after the new bridge is completed, Executive Order 05-05 still applied. Under this process, WSDOT has continued to keep the consulting parties informed of the project. The proposal (not yet finalized) is that the historic bridge will be left standing. The approaching roadway will be removed and the bridge will have bollards installed to keep vehicles off the bridge, but pedestrian access will be provided. The bridge will be inspected every two years and repairs needed will be made "as funding allows." Although this has yet to be formalized, this represents a big step forward to an ultimate solution that would be a win-win solution, providing a new bridge for vehicles, while also preserving the historic bridge.

![]()

Photo Galleries and Videos: McMillin Bridge

Bridge Photo-Documentation

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Bridge Photo-Documentation

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

CarCam: Northbound Crossing

Full Motion VideoNote: The downloadable high quality version of this video (available on the video page) is well worth the download since it offers excellent 1080 HD detail and is vastly more impressive than the compressed streaming video. Streaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Maps and Links: McMillin Bridge

Coordinates (Latitude, Longitude):

Search For Additional Bridge Listings:

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) of this bridge.

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 10 miles (16 kilometers) of this bridge.

Additional Maps:

Google Streetview (If Available)

GeoHack (Additional Links and Coordinates)

Apple Maps (Via DuckDuckGo Search)

Apple Maps (Apple devices only)

Android: Open Location In Your Map or GPS App

Flickr Gallery (Find Nearby Photos)

Wikimedia Commons (Find Nearby Photos)

Directions Via Sygic For Android

Directions Via Sygic For iOS and Android Dolphin Browser

USGS National Map (United States Only)

Historical USGS Topo Maps (United States Only)

Historic Aerials (United States Only)

CalTopo Maps (United States Only)