We Recommend:

Bach Steel - Experts at historic truss bridge restoration.

BridgeHunter.com Phase 1 is released to the public! - Visit Now

Mackinac Bridge

Big Mac / Mighty Mac

Primary Photographer(s): Nathan Holth

Bridge Documented: October 3, 2004 - June 3, 2017

Mackinaw City and St. Ignace: Emmet County, Michigan and Mackinac County, Michigan: United States

Metal 96 Panel Deck Truss Stiffening Wire Cable Suspension, Fixed and Approach Spans: Metal Continuous Bolt-Connected Warren Deck Truss, Fixed

1957 By Builder/Contractor: American Bridge Company of New York, New York and Engineer/Design: David Steinman of New York, New York

Not Available or Not Applicable

3,800.0 Feet (1158.2 Meters)

19,248.6 Feet (5867 Meters)

48 Feet (14.63 Meters)

3 Main Span(s) and 57 Approach Span(s)

24186000000B010

View Information About HSR Ratings

Bridge Documentation

View Archived National Bridge Inventory Report - Has Additional Details and Evaluation

Visit MDOT's News and Info Page For This Bridge

Visit the Mackinac Bridge Authority Website

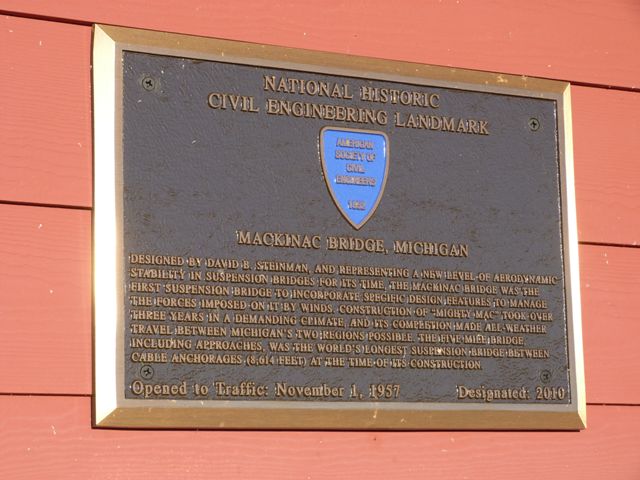

View Detailed ASCE National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark Nomination Authored By Professor Tess Ahlborn, Michigan Technological University

View Historical Article About This Bridge

View Historical Article About David Steinman

A Record-Shattering Bridge

In its own unique way, the Mackinac Bridge is one of the greatest bridges in the world. Aside from perhaps the Great Lakes themselves, the Mackinac Bridge is the most widely recognized landmark in Michigan. It is the largest, most famous, and most historically significant bridge on all of I-75, which runs from Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan to near Miami, Florida. The Mackinac Bridge is the crowning achievement of engineer David Steinman and also one of the greatest construction projects of the American Bridge Company. So significant is this bridge that it became the youngest bridge by far to be listed as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark when it earned that award in 2010. The rest of the bridges to receive that honor dated to before 1940.

The Mackinac Bridge was the longest suspension bridge in the world when first built, a record it held for an impressive several decades. Michigan has been able to claim the longest suspension bridge in the world two times, since the Ambassador Bridge was also the longest in the world when built, although that bridge was quickly surpassed and did not hold the record long. The Mackinac Bridge however was large enough that it held the record for a long time, which shows the scale of the record the Mackinac Bridge broke. In 2010, the Mackinac Bridge remains the longest of its type in the Western hemisphere, and is described as the third longest in the world in terms of total suspension length. The entire bridge weighs 1,024,500 tons.

Although the Mackinac Bridge is no longer the longest in the world, it is worth noting that the success of the Akashi-Kaikyo Bridge in Japan that is today the largest in the world is partly made possible by the Mackinac Bridge. Engineers from Japan traveled to the Mackinac Bridge to learn about working with suspension bridges of this magnitude. They talked with a number of engineers and maintenance workers who were involved with the Mackinac Bridge.

The Mackinac Bridge also set records for safety when it was completed, with extensive stiffening truss, as well as air-flow grating, which reduced the chance of dangerous oscillations to nearly zero. These actions were largely taken in response to the collapse of the 1940 collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

Design of the Bridge and Technical Discussion

Additional Technical Facts

26,372 Feet (8,038 Meters)

155 Feet (47.2 Meters)

552 Feet (168 Meters)

8,614 Feet (2,625.6 Meters)

3 Main Span(s) and 57 Approach Span(s)

2 at 1,700 Feet Each (518.2 Meters)

Compared to other bridges on HistoricBridges.org, this is a relatively new bridge, completely finished in 1958. Its relatively new age in the world of historic bridges evidences itself in its simple concrete approach supports, bolted connections on the stiffening truss, and a lack of v-lacing or lattice on any part of the bridge's built-up steel. However the bridge is old enough that built-up beams were still heavily used for larger beams and rivets were still used to assemble these built-up beams. In contrast, connections on the bridge are bolted, as opposed to riveted. There are reportedly 4,851,700 rivets and 1,016,600 bolts on the bridge. Guardrails are composed of three steel pipes. There is a steel curb that sits in front of the guardrails. Also, the two directions of traffic are separated by only a large steel curb. Open metal grating is located on the inside two lanes, a specifically placed feature to allow air flow through the deck. This open metal air-flow grating, along with the deep, heavy stiffening truss, prevents dangerous oscillations of the deck due to wind. The suspended spans of the Mackinac Bridge contain 186 panels in total. The towers of the bridge were designed with aesthetics in mind, and they include attractive pierced openings in them, in addition to the large openings, which are arched. Approaches to the bridge are deck truss. The southern deck truss approach system is longer than the northern deck truss approach system. There is also a significant causeway built of rubble-type stones on the St. Ignace side of the bridge. A small steel beam bridge is located at one spot on this causeway, to allow water to pass through. Although its original R4 railings are lost and it today looks like an ugly modern bridge, this causeway bridge actually predates the Mackinac Bridge. The causeway originally served the ferry service that preceded the bridge.

David Steinman's Insight Into The Bridge

David Steinman, the engineer for the Mackinac Bridge, was a nationally recognized bridge engineer who had designed many landmark bridges leading up to his design of the Mackinac Bridge. In 1957, Steinman wrote a detailed book called Miracle Bridge at Mackinac. While it is perhaps somewhat biased in favor of the bridge, having been written by the designer of the bridge, the book provides unparalleled insight into the bridge and perhaps the greatest level of detail and discussion of the design of the bridge available. As such, it is a remarkable resource for documenting the bridge. Unfortunately, the book is out of print, and is not digitized by Google. HistoricBridges.org did acquire a copy of the book however, and you may be able to get one from Amazon. In lieu of a free, digital version of this book being made available, HistoricBridges.org is offering some random interesting tidbits, facts, and details about the Mackinac Bridge that this book revealed.

Over the five mile length of the bridge, 27 feet of expansion ability had to be provided. This is to account for movement of the bridge due to environmental conditions, most notably changes in temperature.

The towers of the bridge (referred to as piers 19 and 20) were the deepest caissons ever built for the piers of a suspension bridge.

Steinman and his engineers drew up around 1000 original drawings (such as site plan sheets) for the bridge, and around 3000 additional sheets were drawn up by the contractors (presumably this refers to erection drawings, shop drawings, etc).

Provided expansion for the center suspended span at each end is five feet, eleven inches. The side suspended spans each have been allowed for two feet five inches of expansion. Over the five mile length of the bridge, the combined expansion length provided for is 27 feet. In other words, if all the expansion joints were lined up at the end of the bridge, it would equal the total length of a small bridge! Changes in temperature also cause the length of the main cable to change. In warm weather, this causes the cable to lengthen and thus at the center of the bridge the cable lowers. A distance of up to seven feet (with six feet the typical expected maximum) of cable movement up and down was provided for. The movement of the cable would be even greater if it weren't for the fact that when it warms up, the towers holding the cable become taller, counteracting to a small extent the lowering of the cables.

Appearance of the Bridge

One thing that makes the Mackinac Bridge a winner is its location. Many of the nation's largest historic bridges are located in heavily urban areas such as New York City or San Francisco. Since the Mackinac Bridge is the only large man-made object in the area, and moreover because the surrounding landscape has only low hills, the bridge really sticks out and shows off its size. Also, the way I-75 is curved, if a motorist is heading north, they will not see the bridge at all until they round one final curve and, assuming it is a fairly clear day, the towers are immediately visible, even though still quite distant. Then for the remaining drive to the bridge, the great towers remain visible, beckoning drivers to this stunning landmark. For a first-time experience it is quite a dramatic event. As if that were not enough, there are some of Michigan's old curved t-beam overpasses in this stretch of freeway. Unfortunately, these curved t-beams have lost their beautiful, original R4 type railings. If MDOT were to restore R4 railings to these overpasses, it would bring the beauty of the curved t-beam design back to life, and they would add to the beauty and history of this section of I-75.

The Mackinac Bridge was built after the era of v-lacing and lattice being used on built-up beams. As such, it lacks that form of beauty often seen on historic truss bridges. However, the scale of the bridge is so large that this does not discernably detract from the beauty of the bridge, since the bridge is normally viewed from a distance where v-lacing and lattice would be hard to notice even if it were present.

Condition of the Bridge

This is probably the most cared for bridge in Michigan. Due to the enormous size of the bridge as well as the Mackinac Bridge Authority's commitment to make sure the Mackinac Bridge remains a timeless landmark in Michigan, there is always ongoing maintenance and repair of the bridge, and even painting alone is a constant job.

The Mackinac Bridge is continuously kept in a good condition. The Mackinac Bridge Authority takes a proactive approach to maintenance and preservation. Rather than neglect the bridge to the point that a heavy rehabilitation is needed, they take action as soon as even minor problems develop, or they take preventative measures to keep problems from developing in the first place. This bridge is a model for how all bridges, large and small, should be maintained and preserved. The idea of doing preventative maintenance, and making repairs as soon as problems begin to develop may seem odd in the United States where normally bridges have maintenance and repairs deferred until heavy rehabilitation or replacement is needed. However the Mackinac Bridge approach is a much better way to approach bridge management, and it is similar to the approach used in Europe, which is noted for its beautifully maintained historic bridges.

Tolls provide a solid source of income for the bridge. The tolls help keep paint on this bridge and any other repairs that may become necessary. Nobody likes the the out of pocket cost and inconvenience of having to stop and pay money at a toll booth, especially when we already provide the government with tax dollars for roads and bridges. However the hard truth is that these tolls are currently needed to ensure the preservation of this landmark historic bridge. Unfortunately, in the United States, the existing surface transportation funding system at the federal and state level wastes tax payer dollars on demolition and replacement projects, while also not providing sufficient funds to maintain and rehabilitate bridges. If they did provide more maintenance, repair, and rehabilitation funds, the more costly replacement wouldn't need to occur in the first place and tax payer dollars would be saved, perhaps available to fund the maintenance of a bridge like the Mackinac Bridge without tolls. However, until this country's broken surface transportation funding system is reformed from the ground up, keeping the Mackinac Bridge (and many other landmark size historic bridges) operating under its own toll-funded system is without a doubt the best way to ensure that this magnificent wonder of engineering will remain one of the most recognizable landmarks in Michigan for centuries to come.

Mackinac Bridge Photography Tips and Comments

This bridge is so big that it is impossible to get a perfect picture of exactly what the bridge looks like. It can be a surprisingly challenging bridge to photo, especially if you have a certain angle or shot in mind. A few tips and suggestions follow. A traditional mid-span elevation view of the bridge is possible, although you will find that much of the cable and truss detail is lost because you have to be so far away from the bridge to fit it in the frame. Anyhow, a Mackinac Island Ferry is a great way to view the bridge and get these elevation views. When you get to Mackinac Island, the southwest corner of the island offers good distant views of the bridge. If you don't like boats, or you want more time to set up your camera without the motion of a boat ride, take a drive down Boulevard Drive, which is a tiny dirt road that wanders tight along the shore west from St. Ignace. There are excellent photo opportunities all the way along that road, and no houses are in your way. Mackinaw City offers excellent oblique views and views beside the bridge. When here, keep in mind that the approaches are so long that if you want a photo with the suspension spans filling the frame you will likely want a good zoom on your camera. One nice thing about the Mackinaw City side is that there is no causeway, so you can walk right up and under part of the deck truss approach spans for a closer look. Finally, if you want to get good on-bridge photos, consider attending the Labor Day walk, the only time the general public can walk on the bridge.

There are numerous additional places where photos of this bridge can be taken. There are parks on both sides, as well as some lookouts and high spots that offer views of the bridge.

Make It Look Like You Know Your Business

One final note. If you visit this bridge or are talking about this bridge, please note that "Mackinac" is pronounced "Mackinaw." Note that Mackinaw City is spelled with a W at the end, while everything else (the bridge, the island, etc) are spelled Mackinac with a C. Regardless of spelling, all of these places are all pronounced "Mackinaw." It is surprising the number of people that do not know this fact.

Information and Findings From MDOT

The five-mile stretch of water separating Michigan's two peninsulas, the result of glacial action some twelve thousand years ago, has long served as a major barrier to the movement of people and goods. The three railroads that reached the Straits of Mackinac in the early 1880s, the Michigan Central and the Grand Rapids & Indiana Railway from the south, and the Detroit, Mackinac and Marquette from the north, jointly established the Mackinac Transportation Company in 1881 to operate a railroad car ferry service across the straits. The railroads and their shipping lines developed Mackinac Island into a major vacation destination in the 1880s. Improved highways along the eastern shores of Michigan's lower peninsula brought increased automobile traffic to the straits region starting in the 1910s. The state of Michigan initiated an automobile ferry service between St. Ignace and Mackinaw City in 1923 and eventually operated eight ferry boats. In peak travel periods, particularly during deer season, five mile backups and delays of four hours or longer became common at the state docks at Mackinaw City and St. Ignace. With increased public pressure to break this bottleneck, the Michigan legislature established a Mackinac Straits Bridge Authority in 1934, with the power to issue bonds for bridge construction. The bridge authority supported a proposal first developed in 1921 by Charles Evan Fowler, the bridge engineer who had previously promoted a Detroit-Windsor bridge. Fowler's plans called for an island-hopping route from the city of Cheboygan to Bois Blanc, Round, and Mackinac islands, thence to St. Ignace, along a twenty-four-mile route. The Public Works Administration flatly rejected a request for loans and grants to implement this project. A plan was then drawn up for a direct crossing from Mackinaw City to St. Ignace, but they were again denied funds. In 1940, a plan was submitted for a suspension bridge with a main span of 4600 feet. This design was a larger version of the ill-fated Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington State, a structure destroyed by high winds on November 7, 1940. Although the disaster delayed any further action, the activities of 1938-1940 nevertheless produced some important results. The bridge authority conducted a series of soundings and borings across the straits and built a causeway extending out 4200 feet from the St. Ignace shore. The Second World War ended any additional work, and the Legislature abolished the bridge authority in 1947. William Stewart Woodfill, president of the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, almost singlehandedly resuscitated the dream of a bridge across the Straits of Mackinac. Woodfill formed the statewide Mackinac Bridge Citizens Committee in 1949 to lobby for a new bridge authority, which the legislature created in 1950. A panel of three prominent engineers conducted a feasibility study and made recommendations to the bridge authority on the location, structure, and design of the bridge. The State Highway Department, which had just placed a $4.5 million ferryboat, Vacationland, into service at the straits in January 1952, remained hostile to the bridge plan. In April 1952, the Michigan legislature authorized the bridge authority to issue bonds for the project, choose an engineer, and proceed with construction. The authority selected David B. Steinman as the chief engineer in January 1953 and tried unsuccessfully to sell the bridge bonds in April 1953, but by the end of the year, the authority had sold the $99.8 million in revenue bonds needed to begin construction. The major construction achievement of 1954 was the erection of the bridge's six principal piers, including those for the two towers, the anchorages, and the backstay spans. Enormous steel caissons were sunk into the mud under the straits and then driven to bedrock. After removing all the mud and loose rock, two reinforced concrete piers, which extended to bedrock, more that 200 feet below the water's surface, were poured. In 1955, the remaining twenty-eight piers were built and the anchorage was completed. The Mackinac Bridge began to take shape in 1956, when the main cables were strung and the twenty-eight truss spans that made up the approaches were built. The four-year construction effort ended in 1957, with the erection of the main suspension span and paving of the roadway. The new bridge opened to traffic on November 1, 1957, although the contractors did not complete all the work until September 1958. The official bridge dedication ceremonies began on June 25, 1958, with the first "Governor's Walk" across the bridge, and ended four days later. The annual Mackinac Bridge Walk began as a walking race sanctioned by the International Walkers Association. The first walk, in June 1958, involved only sixty walkers. Later bridge walks took place on Labor Day and the number of participants increased rapidly from about 2500 in 1962 to more than 15,000 in 1966-1968. Since the first "Governor's Walk" at the bridge opening, it has become a mandatory political event for governors and gubernatorial candidates. In 1970, more than 20,000 completed the walk and the numbers reached 70,000 in 1990. The Mackinac Bridge Walk is as much an integral part of Labor Day in Michigan as parades and picnics. The sheer size and beauty of the Mackinac Straits Bridge still impress first-time viewers. The bridge's total length, 8614 feet, the longest in the world, combined with towers standing 552 feet above the water line, a 155 feet clearance under the bridge, and a total weight of 11,840 tons, is indeed an impressive sight. |

Above: 1957 advertisement featuring bridge.

Above: 1957 advertisement featuring bridge.

![]()

Photo Galleries and Videos: Mackinac Bridge

2017 Photos

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2017 Photos

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2011-2014 Structure Overview

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. Includes night photos of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2011-2014 Structure Details

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. Includes photos of bridge plaques. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2011-2014 Structure Overview

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. Includes night photos of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2011-2014 Structure Details

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. Includes photos of bridge plaques. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Additional Bridge Photo-Documentation

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos from before 2011. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Additional Bridge Photo-Documentation

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos from before 2011. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Frank Glover's Journey Under The Bridge

Frank Glover supplied this unique gallery of photos, taken in the 1980s on an ice cutter on a winter day. This photo gallery contains a combination of Original Size photos and Mobile Optimized photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Crossing The Bridge

Original / Full Size PhotosA series of photos taken with a high resolution, wide angle GoPro camera showing the experiance of driving over the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Crossing The Bridge

Mobile Optimized PhotosA series of photos taken with a high resolution, wide angle GoPro camera showing the experiance of driving over the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

CarCam: Southbound Crossing

Full Motion VideoNote: The downloadable high quality version of this video (available on the video page) is well worth the download since it offers excellent 1080 HD detail and is vastly more impressive than the compressed streaming video. Streaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Northbound Crossing

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Civil Engineering Landmark News Story

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Maps and Links: Mackinac Bridge

Coordinates (Latitude, Longitude):

Search For Additional Bridge Listings:

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) of this bridge.

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 10 miles (16 kilometers) of this bridge.

Additional Maps:

Google Streetview (If Available)

GeoHack (Additional Links and Coordinates)

Apple Maps (Via DuckDuckGo Search)

Apple Maps (Apple devices only)

Android: Open Location In Your Map or GPS App

Flickr Gallery (Find Nearby Photos)

Wikimedia Commons (Find Nearby Photos)

Directions Via Sygic For Android

Directions Via Sygic For iOS and Android Dolphin Browser

USGS National Map (United States Only)

Historical USGS Topo Maps (United States Only)

Historic Aerials (United States Only)

CalTopo Maps (United States Only)