We Recommend:

Bach Steel - Experts at historic truss bridge restoration.

BridgeHunter.com Phase 1 is released to the public! - Visit Now

Johnson Street Bridge

Blue Bridge

Primary Photographer(s): Nathan Holth

Bridge Documented: August 25, 2014

Victoria: Capital District, British Columbia: Canada

Metal Rivet-Connected Warren Through Truss, Movable: Single Leaf Bascule (Heel Trunnion) and Approach Spans: Metal Deck Girder, Fixed

1924 By Builder/Contractor: Canadian Bridge Company of Walkerville, Ontario and Engineer/Design: Strauss Bascule Bridge Company (Strauss Engineering Company) of Chicago, Illinois

1979

148.0 Feet (45.1 Meters)

376.0 Feet (114.6 Meters)

Not Available

1 Main Span(s) and 3 Approach Span(s)

Not Applicable

View Information About HSR Ratings

Bridge Documentation

This bridge no longer exists!

Bridge Status: Replaced and demolished in 2018.This Extremely Rare And Significant Heritage Bridge Was Demolished And Replaced!

View a Strauss patent for a bascule bridge similar to the Johnson Street Bridge

Visit Johnsonstreetbridge.org, a website promoting accurate information, public involvement, and preservation.

Visit Johnsonstreetbridge.com, the official demolition and replacement project website.

View a detailed heritage assessment and historical narrative for this heritage bridge.

View official bridge inspection and condition assessment of this bridge.

View historical articles discussing the construction of this bridge.

Johnson Street Bridge: One of Canada's Most Significant Movable Bridges

The Johnson Street Bridge is a rare surviving example of a Strauss bascule bridge in Canada that was actually designed by Joseph Strauss. Some bridges are "Strauss bascule bridges" by design but were not designed by Strauss himself. Additional rarity and significant arises from the fact that the bridge features an overhead counterweight. Most bascule bridges have counterweights located in a pit underneath the road. As if that were not enough significance the Johnson Street Bridge features an extremely unusual leaf design. While the bridge is a single leaf bascule bridge, the bridge is essentially two single leaf bascule bridges side by side sharing a single abutment and an identical design, except that one serves a railroad line and is more narrow. As such, it is possible to raise one bridge and not the other, although obviously both bridges must be raised to allow boats to pass under. There are photos showing one half raised and the other one not available in the photo gallery. This two-bridge configuration is exceedingly rare. Another example is the Michigan Avenue Bridge in Chicago, although this is a double-lead bascule, and each of the two bridges is identical in dimensions and each bridge serves vehicular traffic, but the double-bridge concept is the same. HistoricBridges.org is unaware of another bridge quite like the Johnson Street Bridge where the two bridges are of differing width and one serves a rail line. Given the multiple levels and layers of historic and technological significance that this bridge displays, as well as the lack of a national bridge inventory listing all bridges in Canada to determine the absolute rarity of the bridge, the structure should be considered one of the most important movable bridges in Canada, a nationally significant bridge. The small numbers of surviving examples of this type of bridge in the United States suggest that it should be considered extremely rare in Canada as well. Someone came up with a count of 30 bascule bridges in Canada, but the fine print said the list was an old one and some of them might not be extant today. Therefore, that list should be discounted and the bridge should be considered more rare than that.

The Johnson Street Bridge was designed by renowned engineer Joseph Strauss, one of the most important and prolific movable bridge engineers of the 20th Century. A history of Strauss courtesy of Historic American Engineering Record is offered at the end of this page.

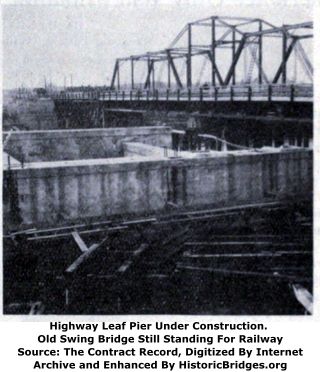

The existing heritage bridge replaced a center-pier swing bridge with a pin-connected through truss design. This history is typical of crossings with movable bridges, since swing bridges were the most common pre-1900 bridge type, but as the 20th Century began, the bascule bridge became the movable bridge of choice due to its ease of operation and lack of navigation obstruction.

The manner in which the bridge was replaced may partially explain why the bridge operates with two independent, parallel leaves. When the bridge was built, the railway continued to use the old swing bridge while the highway leaf was constructed. Railways were always very particular about maintaining traffic flow even during construction projects including bridge replacements. The process of working on the highway portion of the bridge before dealing with the railway portion may have reduced delays.

Since 1979, the bridge has had its attractive sky blue color which has led to some calling the bridge simply the "Blue Bridge"

Preservation: Absolutely Feasible!

There were some comments in the media and public that the bridge could not be safely retrofit for earthquakes. There have been comments that the bridge has ended its service life and cannot be preserved in a way that would offer function for a long time into the future. These suggestions are absurd. A process to retrofit the Johnson Street Bridge was actually proposed in the report on the bridge. However, if that is not enough proof, consider an example. One of the few known surviving examples of a bridge following the design of the Johnson Street Bridge has been retrofitted and preserved in San Francisco, California. It is the Lefty O'Doul Bridge on 3rd Street, designed by Strauss just like the Johnson Street Bridge, and it is very similar to the Johnson Street Bridge except that it lacks the extremely rare two-bridge design seen on Johnson Street. For those who don't know, San Francisco is notorious for having numerous earthquakes some of them being extremely powerful. The city has lost many lives to these earthquakes, some of these due to the collapse of bridges or expressways. Given this, it is safe to assume that San Francisco would never preserve a historic bridge if they thought it could not be made safe from earthquake damage. Yet they found the Lefty O'Doul Bridge feasible to preserve. There is no reason not to think the same for the Johnson Street Bridge.

Another example is the Michigan Avenue Bridge in Chicago. Located in one of the largest cities in the United States, and serving one of its busiest streets, this bridge has been preserved. In the most recent preservation project, the city made a wonderful (if unusual) decision to remove the "modern" railings that had been placed on the bridge years ago and create replicas of the ornate and decorative original railings to put on the bridge. The Michigan Avenue Bridge is one of the most photographed and well-known landmarks in the city, despite the fact that Chicago has more movable bridges than any city in the world, and most of them being old and with heritage value. If preserved and promoted as an attraction, the Michigan Avenue Bridge suggests the potential of a preserved Johnson Street Bridge.

At the same time, it is worth noting that historic bascule bridges, particularly true Strauss bascule bridges with overhead counterweights like Johnson Street Bridge are becoming more rare. The Chelsea Street Bridge in Boston, Massachusetts is currently part of a demolition and replacement project. This makes the Johnson Street Bridge even more important to preserve.

Victoria and its hired engineers are not trying hard enough to design a quality and feasible rehabilitation project. The example rehabilitation that was used to assess the feasibility and value of preservation was a poorly designed rehabilitation that undoubtedly provided an unclear visualization of how feasible preservation really is. For instance, engineers claimed the only way to strengthen the members of the bridge was to weld ugly plate steel on top of the beautiful lattice on the members, then they proceeded to use this false theory to show renderings of how ugly the bridge would look with that alteration. This is not the only way to strengthen beams! There are steel beams that can be inserted inside these beams which would provide great strength with little to no visual impact, since the v-lacing and lattice can be re-attached after beam insertion, and the appearance ends up unchanged. It is hard to believe that none of these engineers thought of this simple and effective solution, that may in fact offer an even greater enhancement to strength than plate steel would. This was done with the Neshanic Station Bridge in New Jersey. How can Victoria declare preservation not worthwhile when the parameters of a quality preservation project have not even been considered? Also, engineers discounted rehabilitation because it would require altering the original appearance of the substructure. However, traditionally, the majority of historic significance in a bridge is derived from the superstructure. Thus, replacement of the substructure is not a major concern as long as the distinctive truss bascule superstructure is retained. Rehabilitation has wrongly been branded by Victoria and consulting engineers as not worthwhile and not fiscally responsible. HistoricBridges.org strongly disagrees with this assessment, based on successful projects elsewhere.

Finally there has been an attempt to claim that rehabilitating the existing bridge would "cost" or "use" more raw energy/resources than replacement and thus would be more adverse to the environment. However the system used to determine this is unclear, and therefore has little merit in our view. Typically, rehabilitation is far less harmful to the environment, especially considering the waste generated by a demolition of the historic bridge, and the energy spent to melt the bridge down for scrap. Finally, one must consider the symbolic value of rehabilitating the existing bridge, which symbolizes the value of sustainability, as opposed to a new bridge which symbolizes a materialistic throw-away society that has no regard for taking care of what we already have. It is difficult to calculate the symbolic environmental value gained from rehabilitating the bridge.

Design/Service Life: A Bunch of Nonsense!

HistoricBridges.org is tired of hearing engineers condemn a preservation project and promote a new bridge by touting their new modern bridges as lasting 100+ years and claiming a rehabilitation will last less long. This was done with the Johnson Street Bridge. This nonsense goes on in the United States all the time and it is very frustrating. The facts speak for themselves. Bridge built since the 1960s are not lasting anywhere near as long as bridges built before that time. In the United States, expressway overpasses from the 1960s and 1970s are frequently being replaced. There was even a bridge from the 1980s that already had to be closed to all traffic due to deterioration. Moreover, successful bridge preservation projects show that old, historic bridges can have a service life far beyond 100 years. Look at the 1901 Cortland Street Bridge in Chicago... or any of Chicago's historic bascule bridges for that matter.

Joseph Strauss, the engineer of the Johnson Street Bridge said the following of the Golden Gate Bridge, which he also engineered: Finally Strauss came to A.P. Giannini, founder of Bank of America. Giannini also had a vision -- of serving fully California's growth. Giannini asked one question: "How long will this bridge last?" Struass replied, "Forever!" If cared for, it should have "life without end." Consider this quote, which thus far has been proven true based on the excellent condition of the Golden Gate Bridge (another old, retrofitted bridge safely carrying traffic in a seismically active city). First, one of the most important ways to have a long-lived bridge is to maintain it. HistoricBridges.org strongly believes that quality and frequency of maintenance and repair more strongly dictates bridge service life than any implied concept of design life. Engineers like Joseph Strauss built quality. Why would any engineer want to put a clock on the life of their bridge? The Johnson Street Bridge is composed of steel trusses just like the Golden Gate Bridge's stiffening trusses. Like the Golden Gate Bridge, they should last nearly indefinitely if maintained and rehabilitated as needed. Design life is largely an excuse to use when a bridge deteriorates prematurely due to a lack of maintainance.

The New Bridge: The Right Thing For Victoria?

The proposed modern replacement bridge is nothing short of bizarre, with a design that looks unbelievable, almost like it defies gravity. Its strange curves and proportions are very modern. Granted, the proposed design isn't a typical boring modern slab of concrete, so perhaps it is a step forward in terms of modern bridge design. But does this modern bridge design fit in Victoria? Does it provide Victoria with the image the city wants? Does it offer any heritage value? Does it offer a long-term source of tourism dollars? Does it mitigate the loss of heritage and culture that will result from the demolition of the existing heritage bridge. HistoricBridges.org strongly believes the answer to all of these questions is a resounding "No!"

Victoria currently possesses an extremely rare and historically significant movable bridge that also has considerable beauty and aesthetic value.

Does a new bridge with an ultra-modern design fit with the

image of Victoria? Consider the following statement from the official city

of Victoria website:

"Much of Victoria's lasting charm and character

stem from its unique collection of well-preserved historic buildings, many

of which date back to the earliest days of settlement in British Columbia.

Our superb examples of turn-of-the-century architecture create a sense of

pride among their owners and throughout the community. These heritage

buildings are symbols of permanence and stability in an ever-changing world.

The City of Victoria is committed, to the preservation of its heritage and

this package describes the policies and facets of that commitment. The City

of Victoria is committed to the conservation of built heritage."

The

planned demolition of one of the most important movable bridges in Canada

hardly seems to be a commitment to the conservation of built heritage.

Further, in a city with such rich heritage as outlined above, the historic

Johnson Street Bridge would be the best fit for this type of city: one with

many heritage buildings and structures. A preserved historic Johnson Street

Bridge would fit within the context of the city it serves, particularly

considers the part of the city which the bridge connects. The demolition of

the heritage bridge and placement of a modern bridge would result in a

strong sense of discontinuity in the city between the heritage of remaining

structures and and would give an impression of a city that believes that

moving forward into the future requires destroying the heritage of the past.

This sense of discontinuity would be felt very strongly with a replaced

Johnson Street Bridge because crossing the bridge drops travelers off in a

very old section of

downtown Victoria that is largely unaltered by modern buildings.

This section of the city is dominated by

well-maintained historic

buildings and the existing heritage bridge fits extremely well with this

context.

The following comment is made by the city in support of the new bridge: "The "wings" of the rolling bascule concept have been designed as a truss system, which also mimics the existing Johnson Street Bridge." The modern bridge's trusses mimic the historic bridge's? Would the city also agree that Victoria, BC mimics Toronto, ON? They are after all, dense urban areas and are both the capitals of a province. Would the city of Victoria agree that if you have visited the city of Toronto, then there is no reason to visit Victoria because Victoria mimic Toronto and thus doesn't offer anything different? Does that comparison sound ridiculous? Certainly! Some people might even describe that comparison as insulting to the unique aspects of each city. Similarly, comparing the modern bridge to the historic bridge is equally ridiculous and even insulting to the design and heritage of the existing bridge.

The proposed replacement bridge's trusses have no more in common with the heritage bridge's trusses than do roof trusses in a house. They may be trusses by definition, but beyond that there is not a single thing they have in common. There is no heritage value in the new bridge. Moreover, the type of beauty seen in the Johnson Street Bridge will be lost forever, since the building techniques used in the Johnson Street Bridge are not used in construction any more. These lost construction techniques include the use of built-up beams. Old built-up beams are so much more beautiful than a modern rolled i-beam or even a modern built-up beam, because attractive lattice and v-lacing were riveted to different rolled sections to produce the built-up beams. V-lacing and lattice contribute greatly to the intricate geometric beauty of a bridge like the Johnson Street Bridge. V-lacing and lattice ensure that a bridge that looks nice from a distance looks even better up close, by revealing an intricate attention to detail that is not found in modern bridges like the one proposed at Johnson Street.

Most modern bridges are plain, simple, and ugly. However, even if the most creative, unique and even aesthetically appealing new bridge is constructed there is one inescapable fact. The modern bridge will have absolutely no heritage value whatsoever, and the proposed Johnson Street Bridge project will destroy every trace of the existing heritage bridge.

Same Game, Different Country

It is most unfortunate, but Canada appears to have fallen prey to the influence of their neighbor, the United States, and forsaken the spirit of heritage preservation that their connection to Great Britain might have once provided and instead taken up the process of blind destruction of heritage structures fully capable of being preserved for continued functional use. Indeed, it is quite disappointing to see how similar Canada's transportation policies are to the flawed policies in the United States. The numbers of the laws might be different (the weak and ineffective historic bridge protections in the United States are called Section 106 and Section 4(f)) but Canada follows nearly the exact same process.

Processes such as an environmental assessment, public involvement, and consideration of alternatives to the demolition of the historic bridge, all familiar to the United States, are followed nearly verbatim in Canada. Just like the United States, these processes are largely treated as a sequence of motions that an owner (city, province, etc) must go through to get to a pre-determined goal: the demolition of the historic bridge. The intent of these processes is to recognize the importance of historic bridges and with that in mind, decide whether or not to preserve the bridge through consideration of alternatives to demolition with true involvement of the public. However, in most cases, the owner already has a demolition goal in mind, and as such, the public involvement and consideration of alternatives have very little meaning. During public involvement meetings, the general public is often presented with official bridge inspection reports with an improper explanation of what these inspections mean. Engineers, expert bridge historians, and others in the transportation profession know how a bridge inspection report is set up. Transportation professionals understand that a bridge inspection report displays photos of the the worst parts of a bridge, even if the majority of the bridge is actually in good condition. However, the public is often unaware of this and they see the inspection document and assume the bridge is about to collapse into the river. This makes preservation often seem less feasible to the general public than it might really be. Worse, these inspection reports often include the recommendation from the inspector on whether the bridge should be replaced or not. Certainly, the inspector has the right to make this recommendation, but when used in public involvement meetings, they may mislead the public into thinking preservation is not feasible when in fact it is. Numerous presentations available for download on www.johnsonstreetbridge.com have slides that only show deterioration on the bridge... largely confined to parts of the truss located below the deck which is typical of most metal truss bridges... but do not show the good condition of the overhead trusses that everyone sees and enjoys as they cross the bridge. This is unacceptable and people need to be informed of both the good and the bad on the bridge, not just the bad, so that a more informed decision can be made.

Worse, with the Johnson Street Bridge, officials are speeding up these processes beyond the normal acceptable speed due to deadlines to secure funding to demolish the bridge. This only further undermines the wise spending of public money and is leading to the unreasonable decision to demolish a beautiful heritage bridge.

With all that said, the end result is that heritage bridges in Canada are being needlessly demolished just like they are in the United States. With the advent of Google Maps Streetsview, anyone can take a virtual tour of Europe for free, and anyone involved with historic bridges in the United States and Canada would do well to check out bridges in Europe, whether virtually on Google or in reality. In Europe, one can find very narrow bridges, and can find extremely old bridges, yet many of these bridges are nevertheless maintained and preserved. Why can't Canada and the United States do this as well? The fact is that we can. Both the United States and Canada would do well to consider following in Europe's footsteps.

HistoricBridges.org Dares You To Do Better: Preserve The Johnson Street Bridge!

HistoricBridges.org often makes the comment that as long as the heritage bridge is still standing, it is not to late to cancel plans to demolish the bridge. Even if the contract is let, a stop work order can be issued. However, from the moment the bridge is demolished, it can never be brought back. Even if a replica was constructed, it would lack heritage value. It is time to halt plans to demolish the existing Johnson Street Bridge and develop a comprehensive preservation plan for the existing heritage bridge. HistoricBridges.org challenges Victoria and challenges the hired consulting engineers: We dare you to do better! The claims that the safety, function, and longevity of the bridge cannot be sufficiently increased as part of a rehabilitation only indicate that Victoria and the hired engineers just are not trying hard enough. A real effort to save this bridge should be made on the part of Victoria. If there is enough creativity to design a bridge as weird and bizarre as the proposed modern bridge, than certainly those same minds can think up a feasible way to preserve the existing heritage bridge while also maintaining a safe and functional crossing.

Information About Joseph Strauss, Engineer For Johnson Street BridgeJoseph Baermann Strauss, Bridge Engineer, and the Strauss Trunnion Heel Bridge - From Historic American Engineering Record Joseph Baermann Strauss (1870-1938) was a talented

and versatile engineer who took his bridge theories and inventions and

applied them to other disciplines as well. Strauss was the son of a

artist and musician and received an engineering degree from the

University of Cincinnati. Upon graduation, in 1892, he worked at the New

Jersey Steel & Iron Company in Trenton, New Jersey and learned all the

aspects of bridge building including designing, estimating and

conducting inspections. During the early part of the twentieth century,

he worked for the Chicago Sanitary District of Chicago and a number of

engineering firms in the Chicago area. During this time he gained a

broad knowledge of railroad bridges and viaducts. Chicago is the home of

bascule bridges due to the Chicago River and the many man-made canals

which run through the city. Strauss soon began to study the dynamics of

moveable bridges and at the same time worked for the Universal Portland

Cement Company. He developed a concrete house for the company and became

familiar with the strength, plasticity and relative cheapness of

concrete as a building material.

In 1902, Strauss formed the Strauss Bascule Bridge Company of Chicago (later

named the Strauss

Engineering Corporation). Through his company Strauss disseminated his

innovative ideas all over

the country. The actual construction of his designs were completed by other

engineering or bridge

fabrication firms. Chiefly A Human Dynamo - Another Biography of Joseph Strauss - From Historic American Engineering Record Biographies of Joseph Baermann Strauss focus on his

five-foot height, as if a

need to

compensate for it motivated his mechanical ingenuity, ceaseless invention, and

political acumen.

On the fiftieth anniversary of San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge, one

publication directly

linked his ineligibility for the University of Cincinnati football team to his

desire "to build the

biggest thing of its kind that a man could build."" But Strauss' success stems

from his keen

understanding of the kinematics of complex moving structures. About 150 patents,

from window

sashes to prison doors, and amusement rides to airplanes, attest to his

obsession with movement

and balance. Some of Strauss' patents cover the use of concrete in structures

and vehicles,

showing a facility with that material as well. These two interests came together

in Strauss' work

with bascule bridges, which started in Chicago and spread throughout the

world. |

![]()

Photo Galleries and Videos: Johnson Street Bridge

About - Contact

© Copyright 2003-2025, HistoricBridges.org. All Rights Reserved. Disclaimer: HistoricBridges.org is a volunteer group of private citizens. HistoricBridges.org is NOT a government agency, does not represent or work with any governmental agencies, nor is it in any way associated with any government agency or any non-profit organization. While we strive for accuracy in our factual content, HistoricBridges.org offers no guarantee of accuracy. Information is provided "as is" without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. Information could include technical inaccuracies or errors of omission. Opinions and commentary are the opinions of the respective HistoricBridges.org member who made them and do not necessarily represent the views of anyone else, including any outside photographers whose images may appear on the page in which the commentary appears. HistoricBridges.org does not bear any responsibility for any consequences resulting from the use of this or any other HistoricBridges.org information. Owners and users of bridges have the responsibility of correctly following all applicable laws, rules, and regulations, regardless of any HistoricBridges.org information.

![]()