We Recommend:

Bach Steel - Experts at historic truss bridge restoration.

BridgeHunter.com Phase 1 is released to the public! - Visit Now

Pont de Québec

Quebec Bridge

Primary Photographer(s): Nathan Holth, Rick McOmber, and Susie Babcock

Bridge Documented: April 14, 2011 and July 7, 2019

QC-175 and Railroad (Canadian National) Over St. Lawrence River (Fleuve Saint-Laurent)

Québec City and Lévis: Capitale-Nationale, Québec and Chaudiére-Appalaches, Québec: Canada

Metal Cantilever Pin-Connected K-Truss Through Truss, Fixed and Approach Spans: Metal Rivet-Connected Warren Deck Truss, Fixed

1917 By Builder/Contractor: St. Lawrence Bridge Company of Montréal, Québec and Engineer/Design: George Herrick Duggan, Ralph Modjeski, and Others

Not Available or Not Applicable

1,800.0 Feet (548.6 Meters)

3,239.0 Feet (987.2 Meters)

94 Feet (28.65 Meters)

3 Main Span(s) and 3 Approach Span(s)

Not Applicable

View Information About HSR Ratings

Bridge Documentation

Bridge Status: May 2024: Bridge Ownership By Federal Government of Canada, and a Restoration Plan In Place!

This bridge's song is:

May 2024 Update: A Restoration Plan For The Bridge

In May 2024, the Federal Government of Canada reached an agreement to take ownership of Pont de Québec from CN. At the same time, an outline for restoration of this National Historic Site of Canada has been produced by the federal government, recognizing the importance of this bridge. This groundbreaking development has essentially ended the threat to this heritage bridge, and now a plan is in place to preserve this bridge, one of the most important heritage bridges on the planet, for future generations. The Federal Government of Canada deserves to be thanked for recognizing the significance of this bridge and stepping up to ensure its preservation.

Read the press release from the Prime Minister's office.

Bridge Narrative: Introduction

This bridge is one of the most important and impressive bridges in the world. When this bridge was built it broke the world record for the largest cantilever span, and to this day the bridge is still the longest cantilever span in the world. It will probably never lose this recognition since metal truss bridges and cantilever bridges are not built anymore today. Cable stayed bridges and pre-stressed concrete bridges may continue to break records and knock one another off the record charts as the years go by, but Pont de Québec will continue to stand as the longest cantilever truss bridge ever built. The bridge is recognized as an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark and is a National Historic Site of Canada.

No work of fiction could ever hope to match the epic story of this bridge's construction. The story is one of engineering innovation, perfection in craftsmanship, hard work, as well as the will to accomplish something so very difficult, even with repeated tragedy. Thanks to coverage of the construction of this bridge by the press of the day during the years in which it was built, as well as the modern day benefits of expired copyrights and digitization by companies like Google and the Internet Archive, HistoricBridges.org is able to offer a detailed history of this bridge complete with historical photos and diagrams. This history is offered below, as well as a contemporary look at the bridge, and finally a list of links to various materials relating to the bridge, including those used to bring these photos and information to you.

A Bridge Is Contemplated

The first serious talk of building a bridge at this location dated to the late 1800s. In 1884, a proposed bridge design was submitted by James Brownlee, A. Luders Light, and T. Claxton Fidler. The design was quite bizarre in appearance compared to any other cantilever truss ever built in North America, but its appearance and design had some similarities to other early cantilevers built outside of North America. This proposed bridge never went beyond discussion and drawings, however. Construction of a bridge would not be attempted until the 1900s.

Artist Rendering of Bridge Proposed In 1884.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

A Tragic Attempt To Bridge The River: The First Bridge

The bridge seen today is sometimes referred to as the "second bridge" or the "new bridge." This is because prior to the construction of this bridge, a previous attempt had been made that resulted in one of the most tragic and well-known bridge collapses in North American history. This attempt, which collapsed when it was about half complete, is usually called the "first bridge".

Artist Rendering of First Bridge

Source:

Engineering, Vol 84, 1907. Digitized By Google.

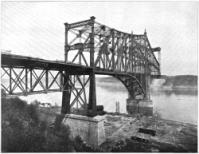

The Phoenix Bridge Company was both the designer and contractor of the first bridge, with the assistance of famous engineer Theodore Cooper. In addition, Peter L. Szlapka was another engineer for the company that was responsible for much of the steel design work. Phoenix Bridge Company was a well-known bridge builder in the late 1800s. Their patented "phoenix column" type of built-up beam was used on the many simple span truss bridges they built, mostly in the eastern United States. Like many bridge builders in this period, the company focused on simple span truss bridges of average lengths, so even the longer bridges the company built were often composed of a series of these simple truss spans. The Walnut Street Bridge in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania is a good example. The company does not appear to have been involved with the design and/or construction of many if any large-scale continuous bridge spans such as a cantilever truss. Aside from having Theodore Cooper do a lot of design work for them, the company appears to have approached the design of Pont de Québec in the way it approached the design of its simple span truss bridges, where the company designed and built the bridges all in-house without cross-checking their engineering work with outside consulting engineers. Theodore Cooper was largely in charge of the whole design process.

Construction of First Bridge and Drawings

Source:

Engineering, Vol 84, 1907. Digitized By Google.

This practice of in-house design and construction was very common for the shorter simple trusses built in the late 1800s. In these situations, a client would approach the company and ask for a bridge with certain dimensions and weight capabilities, and the company would design and build a bridge to suit. It was not as common for large-span bridges however, since such big bridges often required the specialized knowledge that specialized consulting engineers could provide. The practice of in-house design and construction began to decline however in the early 1900s when clients such as government agencies found that the bridge companies were exploiting this system by under-designing bridges to save company costs. As a result, government agencies began to take the roll of designing the bridge (or hiring a consulting engineer) and then they would approach the bridge company with the exact design they wanted and have them build the bridge according to the plans. Given these facts, it seems extremely unusual that in the early 1900s the Phoenix Bridge Company would play this dual roll of design and contractor on its own without any major design from the client or a consulting engineer. Even though the Department of Transport was not involved with the construction of the bridge, it is still unusual when one considers that Québec was a leader in moving away from the in-house system of design under the direction of the first Department of Transport engineer, Gérard Macquet, who was a proponent of designing the bridge and then simply seeking a contractor to build the bridge according to his plans, such that many smaller and older bridges in the province were designed by an agency rather than a bridge building company.

Construction of First Bridge

Source:

1907 "Royal Commission Quebec Bridge Inquiry." Digitized By Google.

A photo of the first bridge that was taken less

than a day before the collapse.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers,

Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

Regardless, the Phoenix Bridge Company designed the first Pont de Québec, and it turns out they did a very poor job of it. The overall bridge design was not strong and massive enough for the crossing, and worse, they used too much material on some members and too little on others, resulting in excessive dead load. The bridge was nearly half completed, when the bottom chord which had been buckling severely, yet was ignored, suddenly failed completely on August 29, 1907, causing complete collapse of the entire structure, sending 75 workers to their deaths. The day of the collapse reads like some outlandish book of fiction. There had been some on-site engineers who were concerned with the issues on the bottom chord. They attempted to take action the day of the collapse to try to halt work. However due to the decision of on-site engineers to try to contact the company headquarters in Phoenixville to halt work on the bridge, thinking that would get results faster, did not work because the person who should have received their message did not happen to be in the office at the right time. Just as all this was happening, the collapse took place, indeed mere minutes before workers would have left the bridge to end the work day. Herein is the additional tragedy of the story: even if the collapse was beyond prevention, if one or two events had realigned by a matter of minutes, the loss of life would have been drastically reduced.

The photos of the collapse are haunting, even if one does not consider the men who were likely crushed to death or pushed underwater beneath the ruins. One of the more dramatic photos is taken from the pier, with the intact bridge plaque visible in the front, and the amazingly nearly unbroken eye bar top chord, which had fallen hundreds of feet, coming to rest on top of the wreckage below.

Collapse of First Bridge

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

Collapse of First Bridge

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

Collapse of First Bridge

Source:

1907 "Royal Commission Quebec Bridge Inquiry." Digitized By Google.

Reportedly, the trusses of the cantilever arm from this bridge remain on the bottom of the deep river to this day. Some sources indicate the bridge parts are partially visible during low tide, although HistoricBridges.org was not able to confirm this during a site visit. The only other original material from this bridge that remains is one of the decorative finials from the bridge, which is preserved as a historical memorial to the people who died during the collapse. It is in the Saint-Romuald cemetery in Saint-Romuald on Rue de L'Église just south of Rue Ouellet. A photo gallery for this is provided, and one photo is visible below.

At least 33 of the workers killed in the collapse were Mohawk steelworkers from the Kahnawake reserve which is located near Montréal. This was a devastating loss to this small reserve. Two steel crosses at each end of the reserve are memorials to these lost lives. One of the crosses can be seen in this Google Streetview. However, a third memorial cross within the Kahnawake Cemetery is unique because it was reportedly made using pieces from the collapsed bridge. Indeed, the cross in the cemetery is of riveted construction, unlike the other two crosses.

Kahnawake

Cemetery Cross

Also in Kahnawake, in 2007, a special memorial was placed in a community park, which has information on the people from Kahnawake who were involved in the bridge collapse, both those who died and survived.

One of the monuments at the Kahnawake Bridge Disaster Memorial

A segment of a documentary available here on YouTube discusses some history of the Kahnawake reserve's connection to steelwork. Many members of this reserve did not just work on Pont de Québec; they had worked on other bridges an structures in the past. In the wake of collapse of the first Pont de Québec, the Kahnawake Mohawks, by then well-known for their skill in erecting high steel structures, went on to participate in the construction of many more structures including the Empire State Building in New York City, and later the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Even today, many Kahnawake Mohawks continue to specialize in steel construction: some of the workers who constructed the One World Trade Center in New York City were Kahnawake Mohawks.

As mentioned, some 75 workers (76 according to other sources) were killed in the collapse of the bridge, the worst bridge construction disaster in history. However, finding a list of who exactly those workers were has proven difficult. The best list available at present is shown below, which is a list of dead, missing, and injured as reported by the Manitoba Free Press on August 31, 1907 and modified and expanded as additional information is discovered. If you have additional information on the people listed below, please contact HistoricBridges.org and let us know and we will update the list. In particular, we would be interested in knowing the full names for people who currently only have initials listed, as well as the type of work they performed on the bridge. Additionally, a website visitor was kind enough to submit a list from an additional source. Click here to view the alternate list.

Dead--

1. Bup. Crolesu, Canadian.

2. Nap Lahache, First Nations.

3. Louis Albany, First Nations.

4. Louis D. Horne, First Nations.

5. James Hardy, Canadian.

6. Angaus Diebe, First

Nations.

7. Wilfrid Prouix, Canadian.

8. Ang. Leaf, First Nations.

9. Zepherin Lefrance, Canadian.

10. Phillip Hardy, Canadian.

11. G. A. Merith, American.

12. Frank Kirby, First Nations.

13. Thomas. B. Jocko, First Nations.

14. Vio Hardy.

The following Americans are missing--

15. B. A. Yensen, general foreman.

16. John L. Worley, assistant foreman.

17. A. H. Birks, civil engineer.

18. J. W. Anderson, assistant engineer.

19. P. C.

Reynolds.

20. Philip Garant.

21. Thomas. Calialian.

22. Carl Swanson.

23. James Bowen.

24. Ira Fast.

25. Harry Briggs.

26. John Edward Johnson (From Buffalo, NY, replaced a man killed during a fall

on August 20, 1907. Riveter/ironworker, body never recovered)

27. A. O. Smith.

28. R. F. Smith

29. A. E. Brind.

The Canadians missing are--

30. Albert Wilson.

31. Jos. Binett.

32. Jos. E. Boucher.

33. Lauret Prouix.

34. George Esmond.

35. Ernest Joncas.

36. Harry French.

37.

Jas. Biron.

38. Gus Wislon.

39. Albert Esmond.

40. Michael Rady.

41. Charles. Hanson.

42. Stanley Wilson.

43. Eug. Derval.

44. Aime Trebel.

45. John McNaughton.

46. Philias Couture.

47. Omer Fontaine.

48. Honore Besudro.

The missing First Nations are--

49. Thomas. L. Deer.

50. Solomon Angus.

51. Louis Diebo.

52. Peter Diebo.

53. Joseph Dove.

54. Louis Lee.

55. Janes Goodlaf.

56. Angus Blue.

57. Joseph French.

58. M. Delialo.

59. Thomas. Bruce.

60. Angus Montour.

61. Jos. Lefebvre.

62. L. M. Jocko.

63. John Jocko.

64. Mitchell Adams.

65. Andrew Rice.

66. James Mitchell.

67. J. C. Morriss.

68. Jos. Dionne.

69. Louis Deer.

Injured--

70. Oscar Laberge, Canadian. (Later Died

From Injuries, Click For Photo)

71. Eugene Lojeunesse, Canadian.

72. Joseph Lajounesse, Canadian.

73. D. B. Haley, Canadian.

74. Ang. Hall, American.

75. Alex, Beauvais, American.

76.

Charles. Davis, First Nations.

77. J. J. Nanto, American.

78. Thomas Montour, American.

Design of the Current Bridge: A Lasting Monument To Span The Centuries

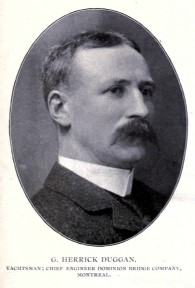

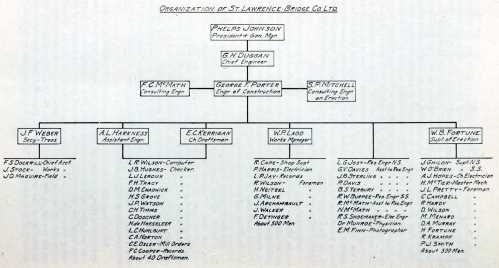

Following the collapse of the first bridge, there was still interest in bridging the St. Lawrence River. This time, the government took control and created a board of engineers to design a new bridge. Among them, was Ralph Modjeski, who is today considered one of the most renowned engineers of the 19th and 20th Centuries. Modjeski specialized in large bridges and was familiar with their nature and design. Modjeski built so many noteworthy landmark bridges that he has been called the greatest bridge engineer in the history of the United States. Other engineers were involved on the project, and some were a part of the project for only part of the time during which the bridge was designed and built. Some other engineers stand out as particularly noteworthy. The Chairman of the Government Board of Engineers was Étienne Henri Vautelet. Robin Vautelet Michetti's is the granddaughter of Étienne Henri Vautelet, and Robin was kind enough to contribute several interesting letters which can be viewed here, which offers a rare look into some of the dialog between the board and the Canadian Pacific Railway as the process of selecting a design for the second bridge took place. Another notable engineer associated with the bridge was Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice, who had previously been an apprentice to Benjamin Baker, who was one of the designers of the Forth Rail Bridge in Scotland. As a member of the Government Board of Engineers, Fitzmaurice likely brought knowledge from his involvement working on what was then the largest cantilever span in the world. Charles N. Monsarrat was a well known Canadian engineer who became the chairman and chief engineer of the board of engineers. Charles C. Schneider was another member of the board of engineers who included work on the erection of the Statue of Liberty in New York City in the United States, and also the Niagara Cantilever Bridge over Niagara River near the Falls. Phelps Johnson, the president of the prolific Dominion Bridge Company of Montréal, headed up the St. Lawrence Bridge Company, under which the the entire design and construction operation would be managed. Johnson is credited with the invention of the K-truss configuration which was first used in Pont de Québec but would go on to be used in other truss bridges in years to come as well. Despite the invaluable contributions of all these men, yet another engineer, George H. Duggan who was from Toronto but had worked as engineer for Dominion Bridge Company, is given credit for a majority of the actual design work for Pont de Québec. Duggan was born September 6, 1862 and died in a car crash in October 8, 1946. Many other engineers were involved, including the president of the Canadian Bridge Company.

In many ways, the work of the bridge under the St. Lawrence Bridge Company was a combination of Canadian Bridge Company and Dominion Bridge Company resources. When the bridge would actually be built, an equally broad number of contractors were involved with the project. The conclusion which can be drawn from all this is that Pont de Québec not only brought together some of the most renowned engineers in North America, but it also brought the involvement of many prolific bridge builders in Canada. Some of the most famous engineers who were involved in the bridge in some manner are highlighted below. Many of these engineers individually are famous for designing many large and important bridges.

Ralph Modjeski, Member of Government Board of

Engineers.

Source: Putnam's Monthly and the Reader, Vol 5,

1908-1909. Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Phelps Johnson, President of St. Lawrence Bridge

Company.

Source: Canadian Engineer, Vol 26,

1914. Digitized By Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Matthew Joseph Butler, Advisor On Selection of

Superstructure.

Source: Canadian Engineer, Vol 26,

1914. Digitized By Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Click here for alternate source with short biography.

Charles

Nicholas Monsarrat, Chairman and Chief Engineer of Government Board of

Engineers.

Source: The Contract Record, 1918. Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Philip Louis Pratley, A Calculating and Designing Engineer for

Government Board of Engineers.

Click image for enlargement with short biography.

Source: The Contract Record, 1918. Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Henry Percy Borden, Member of Government Board of Engineers.

Click image for enlargement with short biography.

Source:

The Engineering Journal, November 1922.

Digitized By Internet Archive and Enhanced By

HistoricBridges.org

Charles Conrad Schneider, Member of Government Board of Engineers.

Click image for enlargement with short biography.

Source: The

Successful American, 1901. Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

George Herrick

Duggan, Chief Engineer of St. Lawrence Bridge

Company.

Source: Men of Canada: A

portrait gallery of men..., 1901. Digitized By Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Click here for alternate source with short biography.

George Frederick Porter, Engineer of Construction.

Click image for enlargement with short biography.

Source:

Who's who in Canada: An Illustrated Biographical Record of Men and Women of the Time, Volume 16, 1922.

Digitized By Google and Enhanced By

HistoricBridges.org

Sir Maurice Fitzmaurice. Member of Government Board of Engineers.

Undated Pre-1924 Photo.

Charles Macdonald. Member of Government Board

of Engineers.

Undated Photo.

Étienne

Henri Vautelet. Chairman and Chief Engineer of Government Board

of Engineers.

Photo Courtesy Robin Michetti.

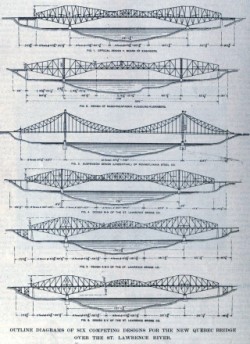

Thought was initially given to salvaging some of the steel, and also reusing the piers from the collapsed bridge. This was soon rejected in favor of redesigning the bridge to be wider and to be designed for greater weight. Numerous designs for the bridge were proposed and studied, both officially with the Government Board of Engineers and the St. Lawrence Bridge Company, and unofficially by engineers in engineering periodicals. Officially, there ended up being six competing designs that the St. Lawrence Bridge Company gave serious consideration to. Among the six designs was one proposed by famous engineer Gustav Lindenthal, which was a suspension span, the only proposal seriously considered that was not a cantilever truss. One of the reasons a cantilever truss was built instead of a suspension span, which tends to be more common for such a vast center span length, is because the cantilever truss provided a more rigid structure, which would have been especially important because of the unique aspects of railroad traffic. It is worth noting however that Gustav Lindenthal had offered a proposed suspension bridge design for the crossing both during planning for the first bridge in 1899, as well as the second bridge in 1910. Another more bizarre option was proposed by another engineer which involved the construction of a deck arch bridge the with an arch span length so long that even today no arch span was ever built so long until 2003 in China. C. A. P. Turner, an American engineer who was known for his developments in the use of reinforced concrete slabs as a bridge superstructure, as well as for his rare Warren-Turner truss configuration even submitted a commentary and suggested design to an engineering periodical.

Proposed Suspension Bridges, 1899 (Top) and 1910

(Bottom)

Source: Engineers and Engineering, Vol 39, 1922. Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Unofficial Bridge Proposal By C. A. P. Turner.

Source: The Contract Record,

Vol 25. Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Proposal

For Arch Bridge At Québec

Source: Engineering News,

Vol 16, No 20, 1910, Digitized By Google

Proposals

Officially Considered.

Source: The Contract Record,

Vol 25. Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

In the end, the design chosen was one developed by the St. Lawrence Bridge Company. The original design offered by the Board of Engineers was rejected as were the many other designs for an unique design that would represent the first noteworthy use of the K-truss configuration, which is used in the cantilever and anchor arms of the bridge's main spans. In this bridge, the K-truss helped make the task of fabrication and erection of the bridge easier. In later years, the K-truss design used at this bridge would later be used for other bridges including cantilever truss bridges and even simple truss spans.

Diagram of St. Lawrence Bridge Company

Organization

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

The significant depth of the St. Lawrence River toward the center of the channel required that the central span be very long so as to locate the piers on the shallower areas toward the banks of the river. Its deck height above the water was dictated by the height of ships passing under it on the critical link in what is today the St. Lawrence Seaway.

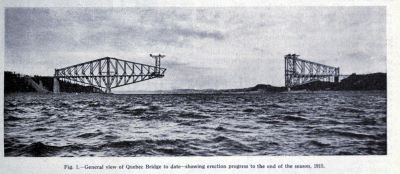

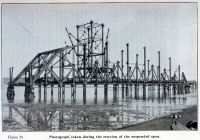

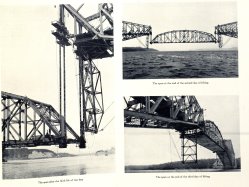

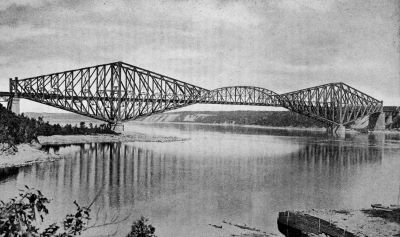

Distant View Showing Bridge Construction

Source: The Contract Record, 1916, Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

As many members this bridge has and as complicated as it looks, the bridge does lack one element that most truss bridges have. On the cantilever and anchor arms, overhead lateral bracing has been eliminated in the design, with only sway bracing and struts present. Lateral bracing under the deck between the bottom chord provides the needed bracing against wind forces. The chosen K-truss design also was a less complex truss configuration than some of the other proposals that had been considered.

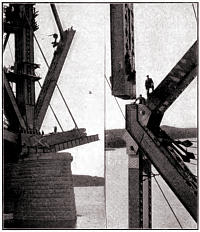

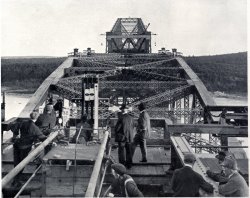

Truss Assembly On Site With Workers Visible For

Scale

Source: "Brooklyn Engineer's Club 1917

Proceedings." Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Riveting Crew

Source: The Contract Record, 1916, Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Construction of an anchor pier for the bridge. Note the eye bar bundles that form the center of the pier.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

As originally built, the bridge weighed 65,500 tons (not counting railroad tracks). Each end post weighed about 400 tons, and the massive vertical members over the cantilever piers, called the vertical posts (or main posts), weighed about 1000 tons each, measuring an impressive 9.2 feet (2.8 meters) by 9.8 feet (3 meters) and being 310 feet (94.5 meters) in height. The bridge included some of the largest truss members ever fabricated in a shop setting at the time. The suspended span of the bridge, if considered its own independent span, was the second longest simple span ever built at the time at 640 feet (195.1 meters), with the Metropolis, Illinois bridge being the only other span of greater length at 720 feet (219.5 meters). It would be decades before a traditional simple span truss bridge would exceed the length of these spans.

Diagram Showing Main Bridge Shop Layout

Source: Canadian Engineer Vol. 26 Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

As a result of the large and unique design of this bridge, a special plant along with special equipment was built for the sole purpose of fabricating the parts of this bridge near Montréal. This was done due to the unusually high numbers of large parts that needed to be made, often in significant quantities as well. An exception was the eye bars of the bridge, which were manufactured in American Bridge Company's company town of Ambridge, Pennsylvania.

Man Standing Next To Bottom Chord In Shop

Source: "Brooklyn Engineer's Club 1917

Proceedings." Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Drilling holes in the shop for a floor beam connection.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

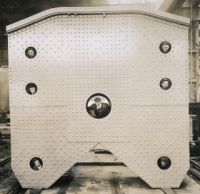

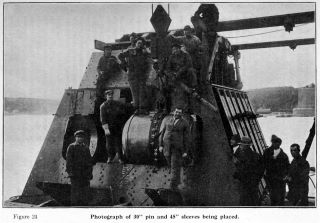

The bridge was so immense in size that it required special effort to fabricate and erect. In the shop, which was specifically designed and built for the construction of the bridge, some of the largest individual metal parts ever fabricated were created. A shoe of the bridge barely could fit within the shop where it was erected. Some pins on the bridge were an amazing 30 inches in diameter.

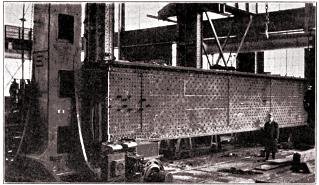

Photos Showing Fabrication of the Bridge In The Shop.

The second photo shows one of the massive shoes for the bridge which would rest on

a pier. The shoe is far taller than the man pictured and it dwarfs the

shop which barely is able to contain it.

Source: Engineering News Vol. 71, 1914 Digitized By

Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

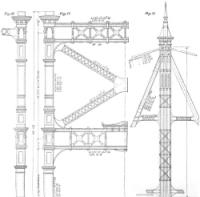

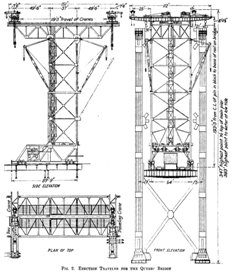

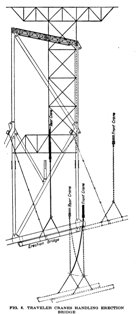

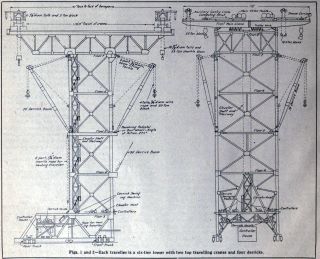

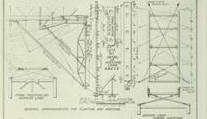

Erection of the bridge involved several interesting aspects, some unique to this bridge, others adapted from the previous bridges including the previous attempt to make Pont de Québec a reality. One of the key erection aspects included the erection traveler, which was an enormous vertical crane structure. Indeed from this traveler crane were several hooks in which to aid the lifting and placement of bridge members. More unusual was the "flying bridge" as it was called which hung from the bridge and held beams, particularly for the bottom chord, in place while they were riveted to the bridge.

Diagrams Showing Erection Traveler

and Flying Bridge

Source: Engineering News Vol. 73, 1915

Digitized By

Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

Diagram of Erection Traveler

Source: The Contract Record, 1918, Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

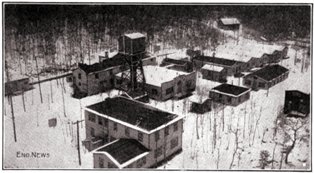

A camp was constructed next to the northern end of the bridge consisting of several buildings to house and serve the needs of on-site workers including foremen, who had their own bunkhouse separate of the workers. The camp included a hospital, a police station, dining hall, and office, a building to distribute pay to workers, as well as other utility buildings.

Layout of Camp At Bridge Site. The office is in the foreground of the

photo, and the plumber shanty in the far back.

Source: Engineering News Vol. 71, 1914 Digitized By

Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

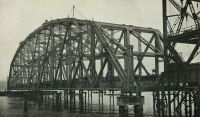

The suspended span of this bridge was assembled on shore, floated out to the center of the river, then lifted into place on the bridge. Because the suspended span was fabricated off site and moved into place on the bridge, it is considered a fabricated part of the bridge, and as such it constituted the largest fabricated metal part ever constructed in the history of the world to that date. Special mooring trusses that looked essentially like pony truss bridges hanging vertically from the cantilever arms were used in conjunction with other mechanical and structural equipment to hoist the bridge into place.

Diagram Detailing Equipment and Process For

Lifting Suspended Span.

Source: Engineering News-Record Vol. 79,

1917 Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Assembling Suspended Span

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Suspended Span Prior To Being Floated Into

Position For Lifting

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Suspended Span Being Floated To The Bridge, Visible In The Distance.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

This innovative method did not work on the first attempt, as the bridge broke free during the process and collapsed into the river below killing thirteen people, marking the second significant and tragic accident in the effort to provide a bridge at this location. Despite the accident, engineers were confident the problem was a one-time event and did not demonstrate a problem with the erection method. Further, unlike the complete collapse of the first bridge, the collapse of the suspended span did not damage the bridge as a whole, and so all that was done was a new suspended span was fabricated and lifted onto the bridge in the same manner. The process was successful on this second attempt. The last step of this process was to drive the last pin into the eyebar hangers. When this was completed, although construction work on the bridge remained, the cantilever structure instantly became a complete, functioning cantilever span, and so at that moment the record for world's longest cantilever span would have been officially broken. The actual time when that final pin driving was noted as 4:00 PM on September 20, 1917.

The Government Board of Engineers reported the list of people who died or were injured during the collapse of the first suspended span as follows:

Dead--

1. C. Bernier,

2. H. Vandel,

3. J. Corbett,

4. M. Regan,

5. M. White,

6. H. Bertrand,

7. Cleophas Cadorette,

8. E. Jourdannais,

9. Sylvian Demers,

10. C. Sweeney,

11. Paul

Laroche.

12. P. W. Rice,

13. W. Dumont.

Injured--

1. L. Jackson,

2. J. Wilson,

3. A. McIntyre,

4. E. McCann,

5. A. Barbeau,

6. E. Normand,

7. D. Lefebre,

8. A. Lafrancois,

9. A. Ford,

10. G. Raymond,

11. A. Anderson,

12. J. Smith,

13. F. Williams.

14. Also, Mr. H. W. McMillan, the Government Board of Engineer's chief shop inspector, also had his leg broken while attempting to reach the end of the cantilevers from the swaying jacking

platforms.

Suspended Span Ready To Be Raised Into Place

Source: Brooklyn Engineer's Club 1917

Proceedings. Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Suspended Span Falling During Accident

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Suspended Span Being Lifted Into Place.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

The four main piers of the bridge have the appearance of stone, but are in fact concrete with stone only placed on the outside facing.

Board of engineers member Ralph Modjeski noted that during the design of the bridge it eventually became clear that although the river was deep toward the center of the bridge which meant that a long span was needed so piers could be placed on the shallower part of the river, the span could have been made shorter than it was. Modjeski however noted that as a project undertaken by a private corporation, the added expense of the longer, record-breaking span would offer more publicity for the endeavor, something desirable to a private corporation. This perspective is a stark contrast to today's 21st Century era of bridge engineering where it is rare that any expense is put toward making a bridge more impressive or attractive. Indeed, it is ironic because Modjeski once commented that in future years he expected engineers to focus more on improving the aesthetic appearance of bridges. He felt bridges of his time were very utilitarian in appearance. Unfortunately, modern bridges built today in the 21st Century are normally so lacking in aesthetic quality that the bridges Modjeski felt were so utilitarian are today beautiful works of art compared to a modern bridge. Even the somewhat graceful 1970 Pont Pierre-Laporte which was built next to Pont de Québec has strikingly unadorned towers and plain and unremarkable stiffening trusses, a strong contrast to the shaped end posts of Pont de Québec and the geometric art of the complex truss design of Pont de Québec.

Sheet From The Bridge Plans Showing A Cantilever

Arm Truss Panel.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol.

2, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

Sheet From The Bridge Plans Showing The

Suspended Span.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol.

2, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

The Experience

As unique and distinctive as the Tower Bridge is to London, and as unique and distinctive as the Brooklyn Bridge is to the United States, so to is Pont de Québec the unique and distinctive bridge icon of Canada. The bridge is truly one of the most historic and greatest bridges ever constructed in the world. Comparing the bridge to the Brooklyn Bridge or the Tower Bridge is appropriate in terms of historic significance. This is evident not only in the record-breaking dimensions of the bridge, but in the complexity of design as well. The immensity of the bridge cannot fully be conveyed on paper or in photos. Only through an actual visit to the bridge can one truly have an appreciation for the scale of what was completed in Quebec.

First Train Crossing The Bridge, October 17,

1917.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

First Freight Train Crossing The Bridge,

December 3, 1917.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

Prince of Wales Dedicating The Bridge, August

22, 1919

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova University

The abundance of caution in designing the bridge is evident in how massive this bridge is. The shear size and complexity of this bridge is incomprehensible. Some of the tension members on this bridge contain no less than twelve parallel eye bars! The a-frame portal bracing on this bridge is enormous. A single beam of the portal bracing is nearly as wide as a whole car. The end posts are considerably wider than a car. The end posts and portal bracings are one of the parts of the bridge which are so large and impressive one cannot help but stare at them.

Two Men and a Floor Beam: In Transport To Site

On Railroad Car

Source: "Brooklyn Engineer's Club 1917

Proceedings." Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Samuel Martindale, aboard the R.M.S Hesperian sailing from Montreal to Plymouth, England took this photo showing the construction of the bridge. He was part of the 35th Battalion's 2nd Reinforcing Draft (Toronto) on his way to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Once he arrived in England he was transferred to, and served with, the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment) in France. He left Montreal on August 17, 1915, took this photo shortly thereafter and arrived in Plymouth on the 28th.

Source: Photo Courtesy, Bryan McCready

A number of members are so large and massive that they feature two rows of lattice instead of the more common single row. Looking far up at the top chord toward the cantilever piers where the main vertical posts are located is dizzying. The top chord of this bridge is composed of impressive bunches of eye bars. Built around these top chord eye bars are Warren trusses which are structurally independent deck trusses which support the inspection catwalks. In other words, there are literally bridges that span the top chord eye bars of this bridge!

Some pins on the bridge are nearly an enormous four feet (1.2 meters) in diameter. The network of sway bracing above the roadway on this bridge is infinitely complex. There are so many braces and trusses composing this bridge that when the bridge is crossed it often feels much more like a tunnel rather than a bridge. Crossing the bridge at night enhances that effect and adds an even more imposing appearance to the bridge than one sees during the day. At the same time, the extensive use of lattice on the bracing of this bridge gives it a light, airy appearance while at the same time still lending even more geometric complexity to the bridge.

Built-Up Beam Assembly In Bridge Shop

Source: The Contract Record, 1918, Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

An additional sense of the mass of this bridge is created by its diamond-shaped cantilever towers composed of the cantilever and anchor arms. The design includes trusses below the deck as well as above. This is a less common design of cantilever bridge, since most through truss cantilever bridges feature trusses only above the deck. In this sense, Pont de Québec is actually a hybrid, with both through and deck truss characteristics. The variable position of the chords which results from this design results in a wide variety of construction details in the truss connections, and even the floorbeam connections to the trusses.

Finally, the central suspended span of this bridge is a structurally independent feature, a large Pennsylvania "Petit" truss which is massive and large in its own right. This suspended span is itself 640 feet (195 meters) in length. On its own, it is among the longest remaining simple truss bridge spans that are older than 1950. The suspended span displays a different bracing configuration which is easy to see when crossing the bridge. The unique experience when on this suspended span is that of being on an separate bridge that would be enormous as a bridge off on is own somewhere, yet it sits as part of a greater cantilever bridge that so so large it dwarfs this otherwise enormous suspended span.

Ralph Modjeski, Member of Government Board of

Engineers

Source: The American Magazine, Vol 92, 1921. Digitized By Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

View Showing Scale Model of Bridge

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

George Herrick Duggan, Chief Engineer of St. Lawrence Bridge Company.

Click image for enlargement with short biography. Source:

Who's who and why, 1920. Digitized By Google.

Phelps Johnson, President of St. Lawrence Bridge

Company. Undated Photo.

Bridge Condition and Recommendations

The bridge was originally a railroad only bridge carrying two sets of tracks, with one lane for vehicular traffic added in 1929. One of the railroad tracks were removed and an additional vehicular traffic lane added in 1949 making it two lanes, and a third lane added in 1993. There were originally two walkways for pedestrians, today there is only one on the eastern side of the bridge.

Despite carrying some vehicular traffic and also receiving government funding assistance, the bridge is wholly owned by Canadian National Railway.

Photo Showing Bridge Construction

Source: Library of Congress.

Photo Showing Erection Traveler On Cantilever Arm

With False Work Also Visible

Source: Engineering News Vol. 76, 1916 Digitized By

Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

Substructure Construction, View Inside Caisson

Source: The Contract Record, 1912, Digitized By

Internet Archive and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org

Normally, a bridge of this size which carries a large volume of traffic would be expected to have some significant alterations, such as the replacement of rivets with bolts, added plate steel, and even reconfiguration or replacement of some members. However this bridge in 2011 retained a remarkable level of historic integrity with no major alterations noted to the trusses at all.

One area of alteration appeared to be the replacement of riveted lattice pedestrian railings with modern railings. However, some of these railing panels were left on the approaches, which allows one to at least discover and observe the type and design of railing that once was on the bridge. The design includes decorative cast posts with lattice railing panels. The lattice is designed in the traditional Canadian style where the lattice bars include the use of angles rather than simple bars as is common in the United States. The Canadian "angle lattice" style appears to have found popular use in Canada because it would have provided a stronger railing that could better resist bending from impact damage.

It was wonderful for HistoricBridges.org to be able to photo-document the bridge in such an unaltered state. The lack of alteration partially speaks to how heavily built-up this bridge is, and also to the quality of the materials and construction. However the lack of alteration also hints at a possible problem because it also suggests that no repairs have been made to the bridge by Canadian National Railway. Over the life of a bridge, even though they may be undesirable from a historian's perspective, repairs and changes are normally needed to keep the bridge in the best condition possible. There do not appear to be any major problems with the bridge, but some minor areas of the bridge were found to have some section loss. These areas could be patched with plate steel or pad welded to fill in the loss.

Photo Showing An Enormous Bottom Chord Section In Bridge Shop

Source: Engineering News Vol. 76, 1916 Digitized By

Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

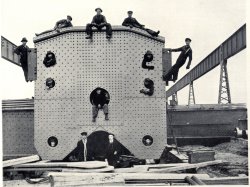

"A 145-ton link for the top of the main post of the second Quebec Bridge

in the St. Lawrence Bridge Company shops. Workmen are appearing in each

hole of the link."

Date: 1915. Source: Eugene Michael Finn/Library and

Archives Canada.

A main post link once again serves as a frame for workers at the fabrication shop.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

Stronger evidence of a lack of preservation commitment on the part of Canadian National Railway (CN) is evident in the fact that in 2005 an in-progress repainting project was halted, leaving the cantilever arms and suspended span with the old greenish paint that is in an advanced state of failure with widespread rust showing, while the anchor arms have a new coat of grey paint. The work was halted apparently because CN was unhappy with some change in the way the federal and provincial financial aid was being provided where they would get 40% aid for the project, which apparently was less than what they wanted. The dispute which ended up in court apparently has not been resolved over six years after the incident began. It is very disappointing to see that CN has chosen to allow the center of the bridge to continue to rust all these years. Even if it ended up costing them more money out of pocket to complete the repainting project, it would be a good public relations gesture that would surely be appreciated by residents and visitors alike. Instead, by halting the project, leaving the center of the bridge to rust and have the appearance of a half-maintained bridge they send the message that they do not care about the wellbeing of one of the most important historic bridges on the planet. It also sends a message that CN does not have respect for the terrible price in human lives that was paid to cross the St. Lawrence River here. Many people died to give the world its largest cantilever truss and as the owner and steward of the bridge CN needs to show this bridge the care, respect, and reverence it deserves.

Photos Showing Erection of Cantilever

Source: Engineering News Vol. 73, 1915 Digitized By

Google and Enhanced By HistoricBridges.org.

Some have called for arrangements and negotiations to take place that would transfer ownership of the bridge back into government ownership, thus making the bridge a publically owned bridge which could then be fully restored under the auspices of government. HistoricBridges.org supports such a move if CN continues to refuse to complete the badly needed repainting project and other needed repairs to the bridge. Given how massive the bridge is as well as the high quality of materials used in this bridge, the section that has not been repainted appears to be holding up fairly well, and there certainly is no concern about the structural integrity of the bridge being compromised at this time. However the longer the bridge sits unpainted, the more it will deteriorate. Increased deterioration will mean increased repair costs down the road, and it will also mean that more parts of the bridge may require more extensive repairs, which would alter the bridge and reduce the excellent historic integrity it maintains today. As such, it is in everyone's interest that the repainting project be completed.

Finally, on another more positive topic it is worth recognizing that one of the most positive aspects about a visit to this bridge is that there is no distasteful cyclone fencing or other sorts of visual and physical obstructions to ruin the view and experience of this bridge, whether you are on the bridge's sidewalk, whether you are beside the bridge, or even below the bridge. This is stark contrast to many large bridges in the United States, or even elsewhere in Canada such as Toronto or Montréal where many of those city have larger bridges which are covered in cyclone fencing, nearly destroying the visual experience of visiting those bridges. It is greatly hoped that Pont de Québec will always remain this free and open, inviting all who see this bridge to come and take a closer look.

View Showing Newly Completed Bridge

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Portal view of the newly completed bridge. Note the original lattice railing, two sidewalks, and no lanes for highway traffic.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

|

Main Plaque 1908 QUEBEC BRIDGE 1918 BUILT FOR THE DOMINION OF CANADA DEPARTMENT OF RAILWAYS AND CANALS RIGHT HON. SIR WILFRID LAURIER P.C. G.C.M.G PREMIER 1896 - 1911 RIGHT HON. SIR ROBERT L. BORDEN P.C. G.C.M.G PREMIER 1911 - HON. GEORGE F. GRAHAM MINISTER OF RAILWAYS AND CANALS HON. FRANCIS COCHRANE " " " 1911 - 1917 HON JOHN D. REID, M.D. " " " 1917 - GOVERNMENT BOARD OF ENGINEERS ON DESIGN, SPECIFICATIONS, AND REPORTING ON SUPERSTRUCTURE DESIGNS SUBMITTED RALPH MODJESKI SIR MAURICE FITZMAURICE CHARLES MACDONALD H. E. VAUTELET CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF ENGINEER OF THE BOARD ADVISING ON SELECTION OF SUPERSTRUCTURE DESIGN M.J. BUTLER C.M.G. H.W. HODGE SUPERVISING DURING CONSTRUCTION RALPH MODJESKI C.C. SCHNEIDER DECEASED SUCCEEDED BY H.P. BORDEN 1916 C.N. MONSARRAT CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF ENGINEER OF THE BOARD APRIL 1911 SUPERSTRUCTURE DEC. 1917 DESIGNED, MANUFACTURED, AND ERECTED BY THE ST. LAWRENCE BRIDGE COMPANY LIMITED MONTREAL, QUE. A COMPANY SPECIALLY INCORPORATED IN THE JOINT INTEREST OF THE DOMINION BRIDGE COMPANY LIMITED LACHINE, QUE. & THE CANADIAN BRIDGE COMPANY LIMITED WALKERVILLE, ONT. TO COMBINE THEIR ORGANIZATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR THE EXECUTION OF THE WORK ORGANIZATION OF THE COMPANY PHELPS JOHNSON PRESIDENT G.H. DUGGAN CHIEF ENGINEER G.F. PORTER ENGR. OF CONSTRUCTION F.C. MCMATH CONSULTING ENGINEER S.P. MITCHELL CONS. ENGR. OF ERECTION W.P. LADD SUPT. OF FABRICATION W.B. FORTUNE SUPT. OF ERECTION THE ST LAWRENCE BRIDGE COMPANY BY THE TERMS OF THE CONTRACT UNDERTOOK THE "ENTIRE RESPONSIBILITY NOT ONLY FOR THE MATERIALS AND CONSTRUCTION OF THE BRIDGE BUT ALSO FOR THE DESIGN, CALCULATIONS, PLANS, AND SPECIFICATIONS." THE "K" SYSTEM OF WEB BRACING USED WAS CONCIEVED BY PHELPS JOHNSON. THE DESIGN WAS DEVELOPED BY G.H. DUGGAN AND WAS DETAILED AND ERECTED BY THE STAFF OF THE COMPANY UNDER THE DIRECT SUPERVISION OF C. F. PORTER JAN. 1910 SUBSTRUCTURE JULY 1914 CONTRACTORS M.P. & J.T. DAVIS S.H. WOODARD SUP'T'G ENGINEER PRINCIPAL DIMENSIONS AND DATES TOTAL LENGTH OF BRIDGE 3229 FEET LENGTH OF SUSPENDED SPAN 640 FEET LENGTH OF MAIN SPAN 1600 " WIDTH C TO C TRUSSES 88 " MEAN HEIGHT ABOVE HIGH WATER 150 " TOTAL DEPTH AT MAIN POST 320 " LENGTH OF ANCHOR ARM 515 " WEIGHT OF STEEL 133,000,000 POUNDS LENGTH OF CANTILEVER ARM 580 " TOTAL VOLUME OF MASONRY 106,000 CU. YARDS CONTRACT FOR MASONRY JAN 10 1910 CONTRACT FOR SUPERSTRUCTURE SIGNED APRIL 4 1911 MASONRY COMPLETED MAY 7 1914 SUSPENDED SPAN COMPLETED SEPT. 20 1917 BRIDGE OPENED FOR TRAFFIC DEC 3, 1917 |

Photos, Historical Reports, and Articles

Photos

HistoricBridges.org completed a full photo-documentation of Pont de Québec that includes a broad set of overview and detail photos that attempts to record both the appearance and construction of the bridge. With a bridge this large, the bridge can look very different when viewed from different angles. Also, because of the way the bridge's cantilever design results in changing member sizes, plus the structurally independent suspended span, there is an immense variety of design details on the bridge. Because of all these reasons, a very large number of photos were needed... particularly detail photos... to give an even somewhat complete photo documentation. As a result, HistoricBridges.org is proud to offer the largest single sets of photo for a single bridge on this website (or perhaps any website), with over 800 photos available.

Additionally, please see this photo gallery on Flickr created by Jean Hemond, Engineer, Photographer, and painter, that shows a number of bridge inspection photos that offer unique angles as well as showing some of the problems that have developed due to the neglect by CN Railway.

In addition, HistoricBridges.org found a number of digitized historical texts relating to the bridge. These texts served as sources for providing the above narrative. They contain additional details and information not covered in the HistoricBridges.org narrative, as well as engineering drawings, historical photos, and other useful materials. The texts are offered below as convenient excerpts from the larger magazines and books from which they were published.

Historical Texts and Photos (Original, Primary Source Materials)

Report of the Government Board of Engineers - Volume 1: This report created by the people who guided and watched over the design and construction of the second bridge is an enormous resource of information, with numerous photos, and a detailed discussion about every aspect of the bridge. Also available for download is a large (over 1gb) zip file of high resolution JPEGs of this book. This book was digitized by Villanova University. HistoricBridges.org greatly appreciates their efforts since this essential text was not digitized by the larger scanning projects run at Google and the Internet Archive and moreover the quality of the scan is very high.

Report of the Government Board of Engineers - Volume 2: This is an appendix that includes copies of the original plans for the existing second bridge as well as plan sheets for the initial proposal for the second bridge as presented by the Government Board of Engineers. Also available for download is a large (over 1gb) zip file of high resolution JPEGs of this book. This book was digitized by Villanova University. HistoricBridges.org greatly appreciates their efforts since this essential text was not digitized by the larger scanning projects run at Google and the Internet Archive and moreover the quality of the scan is very high.

Transactions of the Engineering Institute of Canada - In-depth articles, discussions, drawings, and photographs relating to the second bridge.

Canadian Society of Civil Engineers Discussion - Similar discussion as found in the above articles, but this discussion includes some additional drawings.

Notes on the Construction and Erection of the New Quebec Bridge - A detailed and informative discussion with photos regarding the fabrication and construction of the bridge.

Canadian Engineering - A series of articles, photos, and diagrams relating to the construction of the bridge.

The Contract Record - A series of articles, photos, and diagrams relating to the construction of the bridge.

Article Discussing The New Bridge Design - This brief article discusses the design of the new bridge and compares it to the collapsed first bridge.

Historical Popular Science Article on Second Bridge Construction - Various aspects are discussed, with a focus on the collapse of the suspended span during the attempt to lift it into place.

Engineering News Articles About New Bridge Construction - A series of articles have been compiled here to offer a detailed history including numerous photos of the erection of the second bridge.

Engineering News-Record Article Discussing Raising of the Suspended Span - Discusses the new bridge. Includes photos.

Railway Age Gazette Article Discussing Erection Equipment - Discusses the new bridge. Includes photos and a diagram.

Canadian Railway and Marine World 1917 Article - Overview that discusses the erection of the bridge. Includes drawings and photos.

K-Truss Analysis - This article was written soon after construction of the second bridge, and is a detailed engineer's mathematical analysis of the K-truss.

Proposal For Arch Bridge - This article created prior to the construction of the second bridge but after the collapse of the first bridge was a proposal for a deck arch bridge of unheard of length. Such a length arch was not built until 2003 in China.

Articles About First Bridge - These articles include construction and collapse photos, as well as original plans for the bridge.

Booklet About First Bridge - This booklet has excellent photos of the construction of the first bridge. Its time of publication is somewhat unusual, since it was published in 1907, but before the bridge collapse in August, so the book makes no mention of the collapse. However, the book details construction of the bridge through the completion of the cantilever arm.

Historical Report on First Bridge Collapse: Report on Design of Quebec Bridge Volume 1 - This is the official investigation report following the collapse of the first bridge.

Historical Report on First Bridge Collapse: Report on Design of Quebec Bridge Volume 2 - This is the official investigation report following the collapse of the first bridge. Volume 2 has a wealth of photos of the first bridge in the second half of the book.

Proposal For Bridge - 1885 - This is the earliest known formal proposal for a bridge at this location, dating to 1884-1885.

Ralph Modjeski Articles - Various articles and biographical sketches of one of the most well-known members of the board of engineers, Ralph Modjeski.

Workers Pose For Photo During A 30 Inch Pin

Placement

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

View Showing The Erection "Flying" Bridge

Source: Transactions of The Engineering

Institute of Canada, 1919. Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Further Bibliography

Middleton, William D., The Bridge at Quebec Indiana University Press, 2001 - This is the leading English language modern book about the bridge. It includes a detailed history and discussion, numerous photos, and a comprehensive bibliography (which was of great use in compiling this HistoricBridges.org page). The book may be previewed here, purchased from the publisher here, or purchased through Amazon.

L'Hébreux, Michel., Le pont de Québec, Septentrion, 2001, 2008 - This is the leading French language modern book about the bridge. It appears to offer content similar to the English book. It is written by an expert who has given over 1000 lectures on the bridge. The 2001 edition may be previewed here. The updated 2008 edition is available for purchase in paper of PDF format here.

Passfield, Robert W., "Philip Louis Pratley (1884-1958): bridge design engineer", 2008 - A detailed bibliography of this important Canadian engineer who played a role in the design of the second Pont de Québec. The author, Robert Passfield is a noted historian with his own website.

External Links

Video With Slideshow and Period Motion Picture - This video from www.ameriquefrancaise.org is mainly of interest because it includes video from the construction of the bridge, as well as video of a steam train on the bridge and a steam boat passing under the bridge. There is also video of a 1950s rehabilitation ribbon cutting.

Engineers and Other Noteworthy People Involved

In Bridge Design and Construction

Source: Engineering News-Record Vol. 79,

1917 Digitized By

Internet Archive.

Good historical photos to conclude this narrative, the above pair of photos show

the last lifting link being removed during the raising of the suspended span. To the right is one of the most significant photos taken during the project, which was the final pin connecting the suspended span to the rest of the

bridge. The photo notes the exact time and date of 4:00 PM, September 20, 1917. While more work remained to be done on the bridge in general, this moment marked the actual completion of the cantilever structure, thereby setting the

record of world's longest cantilever span.

Source: Quebec Bridge Report of the

Government Board of Engineers, Vol. 1, 1919. Digitized By Villanova

University

![]()

Photo Galleries and Videos: Pont de Québec

Overview: Elevation

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Beside Bridge and On Sidewalk

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Driving On The Bridge

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Portals, Plaques, and Steel Brands

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Deck Truss

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos that document the deck truss approach spans for the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Details: Anchor Arm

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Details: Cantilever Arm

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Details: Suspended Span

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Bridge Collapse Memorials

Original / Full Size PhotosOverview and detail photos of several different memorials to the tragic collapse of the first bridge, some of which used salvaged parts of the collapsed bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Driving Southbound Across Bridge, 2011

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Driving Northbound Across Bridge, 2019, GoPro Camera

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Driving Northbound Across Bridge, 2019, CamPark Camera

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Driving Southbound Across Bridge, 2019, CamPark Camera

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Driving Southbound Across Bridge, 2019, GoPro Camera

Full Motion VideoStreaming video of the bridge. Also includes a higher quality downloadable video for greater clarity or offline viewing.

![]()

Overview: Elevation

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Beside Bridge and On Sidewalk

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Driving On The Bridge

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Portals, Plaques, and Steel Brands

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Deck Truss

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos that document the deck truss approach spans for the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Details: Anchor Arm

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Details: Cantilever Arm

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Details: Suspended Span

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Bridge Collapse Memorials

Mobile Optimized PhotosOverview and detail photos of several different memorials to the tragic collapse of the first bridge, some of which used salvaged parts of the collapsed bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Guest Photos

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos from other photographers. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Guest Photos

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview and detail photos from other photographers. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Maps and Links: Pont de Québec

Coordinates (Latitude, Longitude):

Search For Additional Bridge Listings:

Additional Maps:

Google Streetview (If Available)

GeoHack (Additional Links and Coordinates)

Apple Maps (Via DuckDuckGo Search)

Apple Maps (Apple devices only)

Android: Open Location In Your Map or GPS App

Flickr Gallery (Find Nearby Photos)

Wikimedia Commons (Find Nearby Photos)

Directions Via Sygic For Android

Directions Via Sygic For iOS and Android Dolphin Browser