We Recommend:

Bach Steel - Experts at historic truss bridge restoration.

Kinzie Street Railroad Bridge

Chicago and Northwestern Railway Bridge

Primary Photographer(s): Nathan Holth

Bridge Documented: August 12, 2006 and 2011-2013

Railroad (Abandoned Union Pacific) Over North Branch Chicago River

Chicago: Cook County, Illinois: United States

Metal 7 Panel Rivet-Connected Warren Through Truss, Movable: Single Leaf Bascule (Strauss Trunnion) and Approach Spans: Metal Girder, Fixed

1907 By Builder/Contractor: Toledo-Massillon Bridge Company of Toledo, Ohio and Engineer/Design: Strauss Bascule Bridge Company (Strauss Engineering Company) of Chicago, Illinois

Not Available or Not Applicable

170.0 Feet (51.8 Meters)

195.8 Feet (59.7 Meters)

Not Available

1 Main Span(s) and 1 Approach Span(s)

Not Applicable

View Information About HSR Ratings

Bridge Documentation

View Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Documentation For This Bridge

HAER Data Pages, HTML - HAER Data Pages, PDF

View Strauss Patent 738954 and Strauss Patent 995813

View Historical Articles About This Bridge And Previous Railroad Bridges At This Location

Historic Significance

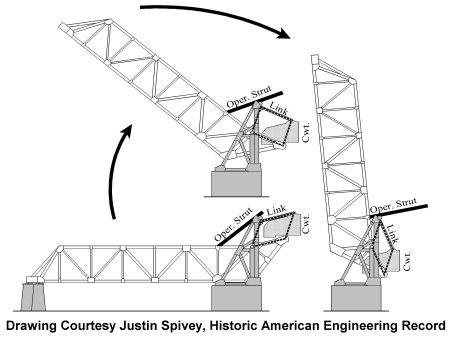

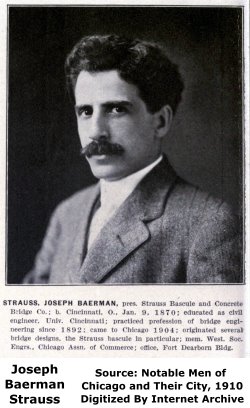

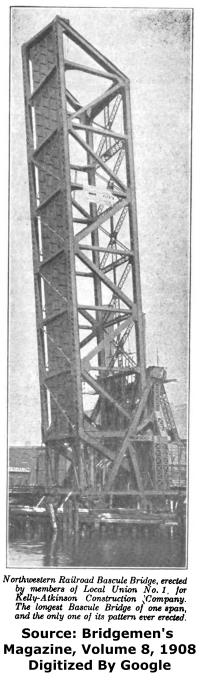

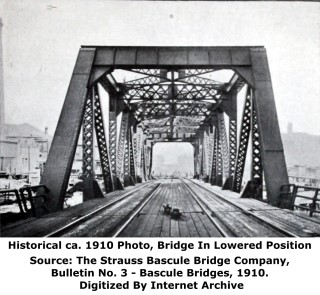

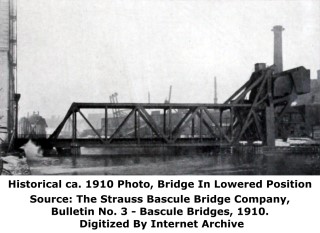

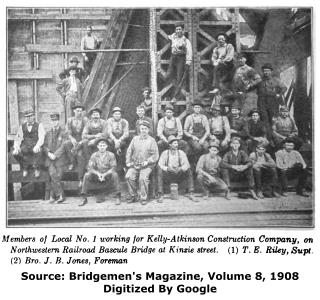

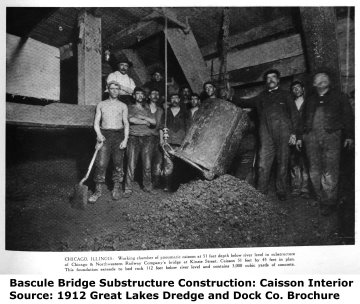

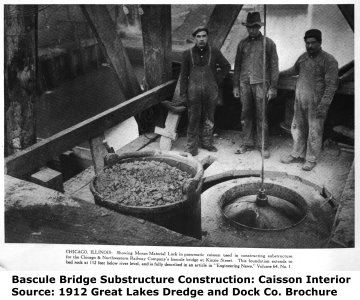

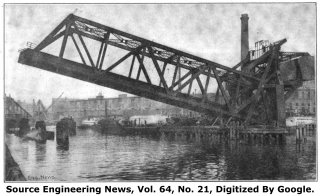

Sitting south of the Kinzie Street Bridge, this railroad bridge is (except for one day each year, discussed later) abandoned in the raised position and is no longer used by trains. Historic American Engineering Record documentation for the bridge discuss the historic significance of this bridge. On aesthetic terms, this strange movable bridge is one of only a few bascule bridges in Chicago where the counterweight is above the ground. More importantly, the bridge employs an unusual counterweight system where the counterweight is not rigidly connected to the bridge and it actually moves independently of the bridge itself. The bridge was built in 1907, with its truss bascule superstructure design being provided by Joseph Strauss, who was an important engineer who worked to develop trunnion bascule bridge designs, and would often be angry at Chicago city engineers since he felt the designs the city was using were to close to his patented designs and even went as far as to take successful legal action against the city. This particular bridge follows unique design of trunnion bascule that Strauss used, which in later bridges eventually evolved into the heel-trunnion type of bascule. This early example could be considered a prototypical example that documents the development of the heel-trunnion type of bascule. The steel superstructure was fabricated by the Toledo-Massillon Bridge Company of Toledo, Ohio. This railroad line was owned by the Chicago and North Western Railway until Union Pacific bought them out in 1995. The substructure for this bridge was designed by William H. Finley, an engineer of the Chicago and North Western Railway. Like the Lakeshore Drive Bridge, this bascule set records when it was built. At the time of its completion, this railroad bridge was the heaviest as well as the longest bascule leaf in the world!

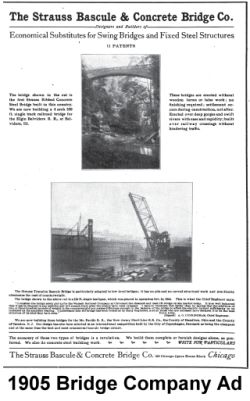

When constructed, the company Joseph Strauss created was called the Strauss Bascule and Concrete Bridge Company. During this time, he built a small number of concrete bridges, notably a couple ribbed concrete arch bridges. However the periodical Industrial World reported in a November 7, 1910 issue that he had changed the name to Strauss Bascule Bridge Company and would no longer build concrete bridges. This is the only movable bridge designed by Strauss remaining in Chicago that dates to before the name change.

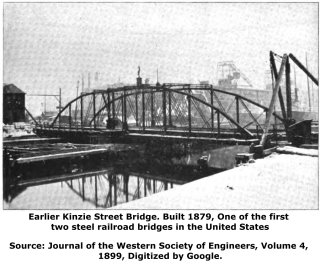

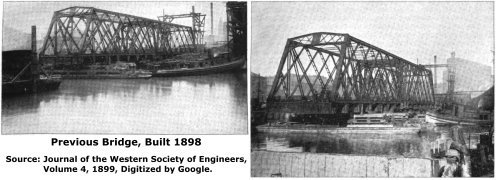

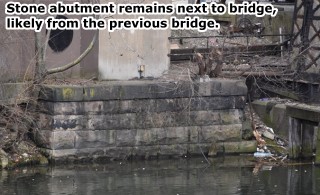

The site of this bridge is a historical crossing for railroads. It is the location of the first railroad bridge in Chicago, dating to 1852, a significant observation given the high level of importance that railroads would play in the development of Chicago in the decades after that date. One of the two first all steel railroad bridge in the country was built here as well in 1879 alongside the Glasgow Railroad Bridge in Missouri.

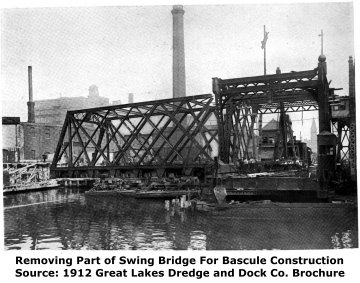

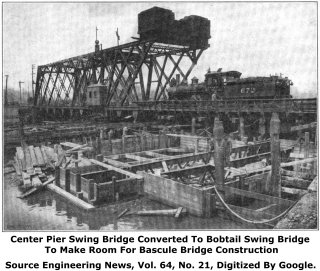

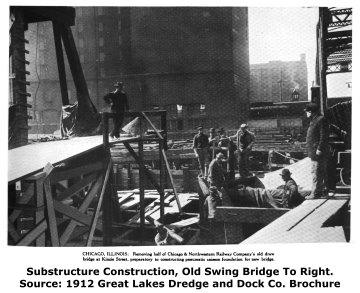

The 1879 bridge was replaced with a lattice through truss swing bridge in 1898. This bridge had a very short life, testimony to the rapidly changing needs of boats and trains during this period of history. The construction of the bascule bridge has an interesting connection to the 1898 swing bridge. Railroads were notorious for devising creative ways to keep their trains (and their profits) rolling even when a bridge was being replaced. Here, the bascule bridge was built directly beside the swing bridge. However, this created a problem. If the swing bridge opened for boats, one end of the swing bridge would crash into the bascule bridge construction site. Engineers solved this problem by cutting this half the swing bridge off and adding a counterweight to that end effectively turning the center pier swing bridge into a bobtail swing bridge

This crossing once served the Wells Street Passenger Terminal of the Chicago and Northwestern Railway. For this reason the railroad and railroad personnel often referred to the bridge as the "Wells Street Bridge" according to Mike D, the last bridge tender to operate this bridge.

An Abandoned Bridge (Almost)

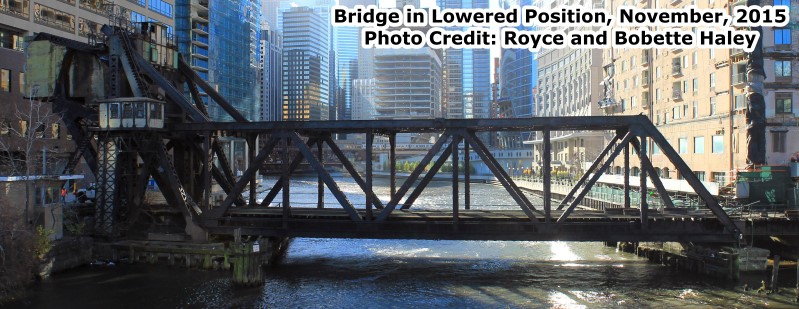

According to Historic American Engineering Record, at the time they documented the bridge, this bridge still lowered once in a while to allow a train to access the Sun Times building to deliver paper, but noted that the newspaper company was going to move its printing operations after which the bridge would be abandoned. Since that time, the bridge has indeed been unused, left standing in its raised position. The bridge itself however is still in good shape with a decent coat of paint on it. The bridge is not "technically" abandoned, however. Once a year, Union Pacific Railroad lowers the bridge for the sole purpose of preventing the bridge from being truly abandoned? Once the bridge is lowered, a company truck is driven over the bridge, which allows the bridge and railroad line to officially remain in an "active status." Additionally, at this time, any repairs needed to ensure the continued ability of the bridge to perform this meager duty are also performed by the crew.

It is not known on what (if any) schedule this annual bridge lowering occurs. As such, this rare event is a sort of historic bridge lottery. The chance that you will randomly happen to visit this bridge at just the right time to witness this event is very unlikely indeed. However, Royce and Bobette Haley won this "lottery" and took a lot of photos, and have been kind enough to share these with HistoricBridges.org. Their photos showing the rare occasion of this bridge in the lowered position are available in the 2015-2016 photo gallery available below. One photo is also shown above.

Bridge Aesthetics and Landmark Status

The Historic American Engineering Record noted that apparently some people feel that this bridge has no aesthetic value and does not blend in with the clean look of the skyscrapers of the city. They note that likely this priceless historic artifact may eventually be scrapped and someone will pick up a few bucks for the steel. This is an absurd idea to for a bridge that is part of the bascule bridge legacy in Chicago. Perhaps if it were painted a lighter color, or a color similar to that of the other highway bridges in Chicago then people would like it more. The reality is that Chicago's unique identity and culture is derived from a fusion of both modern and historical attractions and structures. Chicago's modern attraction, the Trump Tower sits next to the historic Wrigley Tower. Similarly, there is no reason why this historic bridge cannot remain next to any number of modern buildings. Just as Chicago's historic Water Tower sits in the shadow of the Hancock Center as a reminder of the pre-fire Chicago that the current city's towering skyscrapers were built upon, the Kinzie Street Railroad Bridge is a reminder of the industrial past that grew Chicago into the great city it is today.

At the other end of the spectrum, this bridge has been designated a Chicago Landmark. Chicago's Landmark designations are significant because it provides a barrier to demolition. It also is a formal recognition on the part of the city that this bridge does contribute positively to the visual qualities of the area. Anyone wishing to demolish the bridge cannot do so until they convince the city that their reasons for demolishing the bridge outweigh the value of the bridge as a historic and visual landmark of Chicago.

Information and Findings From Chicago Landmarks DesignationGeneral Information Address: South of Kinzie St., East of Canal St.

(North Branch of the Chicago River) This Bridge Is A Designated Chicago Landmark |

Information About Joseph StraussJoseph Baermann Strauss, Bridge Engineer, and the Strauss Trunnion Heel Bridge - From Historic American Engineering Record Joseph Baermann Strauss (1870-1938) was a talented

and versatile engineer who took his bridge theories and inventions and

applied them to other disciplines as well. Strauss was the son of a

artist and musician and received an engineering degree from the

University of Cincinnati. Upon graduation, in 1892, he worked at the New

Jersey Steel & Iron Company in Trenton, New Jersey and learned all the

aspects of bridge building including designing, estimating and

conducting inspections. During the early part of the twentieth century,

he worked for the Chicago Sanitary District of Chicago and a number of

engineering firms in the Chicago area. During this time he gained a

broad knowledge of railroad bridges and viaducts. Chicago is the home of

bascule bridges due to the Chicago River and the many man-made canals

which run through the city. Strauss soon began to study the dynamics of

moveable bridges and at the same time worked for the Universal Portland

Cement Company. He developed a concrete house for the company and became

familiar with the strength, plasticity and relative cheapness of

concrete as a building material.

In 1902, Strauss formed the Strauss Bascule Bridge Company of Chicago (later

named the Strauss

Engineering Corporation). Through his company Strauss disseminated his

innovative ideas all over

the country. The actual construction of his designs were completed by other

engineering or bridge

fabrication firms. Chiefly A Human Dynamo - Another Biography of Joseph Strauss - From Historic American Engineering Record Biographies of Joseph Baermann Strauss focus on his

five-foot height, as if a

need to

compensate for it motivated his mechanical ingenuity, ceaseless invention, and

political acumen.

On the fiftieth anniversary of San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge, one

publication directly

linked his ineligibility for the University of Cincinnati football team to his

desire "to build the

biggest thing of its kind that a man could build."" But Strauss' success stems

from his keen

understanding of the kinematics of complex moving structures. About 150 patents,

from window

sashes to prison doors, and amusement rides to airplanes, attest to his

obsession with movement

and balance. Some of Strauss' patents cover the use of concrete in structures

and vehicles,

showing a facility with that material as well. These two interests came together

in Strauss' work

with bascule bridges, which started in Chicago and spread throughout the

world. |

![]()

Historic Bridges of Chicago and Cook County

Chicago and Cook County are home to one of the largest collections of historic bridges in the country, and no other city in the world has more movable bridges. HistoricBridges.org is proud to offer the most extensive coverage of historic Chicago bridges on the Internet.

General Chicago / Cook County Bridge Resources

Chicago's Bridges - By Nathan Holth, author of HistoricBridges.org, this book provides a discussion of the history of Chicago's movable bridges, and includes a virtual tour discussing all movable bridges remaining in Chicago today. Despite this broad coverage, the book is presented in a compact format that is easy to take with you and carry around for reference on a visit to Chicago. The book includes dozens of full color photos. Only $9.95 U.S! ($11.95 Canadian). Order Now Direct From The Publisher! or order on Amazon.

Chicago River Bridges - By Patrick T. McBriarty, this is a great companion to Holth's book shown above. This much larger book offers an extremely in-depth exploration of Chicago's movable highway bridges, including many crossings that have not existed for many years. Order Now Direct From The Publisher! or order on Amazon.

View Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Overview of Chicago Bascule Bridges (HAER Data Pages, PDF)

Chicago Loop Bridges - Chicago Loop Bridges is another website on the Internet that is a great companion to the HistoricBridges.org coverage of the 18 movable bridges within the Chicago Loop. This website includes additional information such as connections to popular culture, overview discussions and essays about Chicago's movable bridges, additional videos, and current news and events relating to the bridges.

Additional Online Articles and Resources - This page is a large gathering of interesting articles and resources that HistoricBridges.org has uncovered during research, but which were not specific to a particular bridge listing.

![]()

Photo Galleries and Videos: Kinzie Street Railroad Bridge

2015-2016 Bridge Photo-Documentation

Original / Full Size PhotosIncluding photos of the bridge in the lowered position, a collection of overview and detail photos. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

2015-2016 Bridge Photo-Documentation

Mobile Optimized PhotosIncluding photos of the bridge in the lowered position, a collection of overview and detail photos. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Pre-2015 Structure Overview

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Pre-2015 Structure Details

Original / Full Size PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery offers photos in the highest available resolution and file size in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Pre-2015 Structure Overview

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of overview photos that show the bridge as a whole and general areas of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Pre-2015 Structure Details

Mobile Optimized PhotosA collection of detail photos that document the parts, construction, and condition of the bridge. This gallery features data-friendly, fast-loading photos in a touch-friendly popup viewer.

Alternatively, Browse Without Using Viewer

![]()

Maps and Links: Kinzie Street Railroad Bridge

Coordinates (Latitude, Longitude):

Search For Additional Bridge Listings:

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 0.5 miles (0.8 kilometers) of this bridge.

Bridgehunter.com: View listed bridges within 10 miles (16 kilometers) of this bridge.

Additional Maps:

Google Streetview (If Available)

GeoHack (Additional Links and Coordinates)

Apple Maps (Via DuckDuckGo Search)

Apple Maps (Apple devices only)

Android: Open Location In Your Map or GPS App

Flickr Gallery (Find Nearby Photos)

Wikimedia Commons (Find Nearby Photos)

Directions Via Sygic For Android

Directions Via Sygic For iOS and Android Dolphin Browser

USGS National Map (United States Only)

Historical USGS Topo Maps (United States Only)

Historic Aerials (United States Only)

CalTopo Maps (United States Only)